- 1364 views

THE 1878 and 1897 YELLOW FEVER EPIDEMICS

Yellow fever was the scourge of the 19th Century on the Gulf Coast. It was also known as the "saffron scourge", "bronze john", black vomit", and "yellow jack". Ships traveling from the Caribbean region to New Orleans and Mobile often brought the larvae of the Aedes aegypti mosquito in their water barrels. The yellow fever virus, marked by jaundice, high fever, nausea, internal hemorrhaging, and often death, was carried by this tropical insect.

The worst yellow fever epidemic on record occurred in 1853. New Orleans was particularly hit hard that year, as 10,000 of the 30,000 persons infected with the virus died. It earned the Crescent City the epithet "Necropolis of the South". Two other years of pandemic proportions in the Gulf Coast were 1858 and 1878.

The small towns and villages of coastal Mississippi were a popular retreat for those who could afford to leave New Orleans during the "sickly season". This period coincided with the time of greatest fever danger which commenced with the beginning of warm weather in late May to early November, or the first killing frost. Naturally, Ocean Springs was a favorite place to escape the heat, humidity, and general malaise of the Big Easy.

The 1878 Epidemic started at New Orleans in July and took nearly four months to run its course through the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. When it was over, the nation recorded more than 100,000 cases of fever and a mortality estimated as high as 20,000 people. Particularly hard hit were the cities of Memphis (approximately 6,000 deaths), New Orleans (between 4,000 and 5,000 deaths), and Vicksburg where about 1,000 victims fell to the pestilence.

Fever cases and deaths occurred as far north as St. Louis on the Mississippi River and Louisville, Kentucky and Gallipolis, Ohio on the Ohio River. The economic impact to the nation was over $100,000,000 due to the suspension of industry and trade, lost wages, medical attendance, and relief for the thousands of sick and unemployed. It is estimated that New Orleans lost $15,000,000 during the crisis.

By late September 1878, health conditions in Mississippi had gotten so grave that Governor John M. Stone made a proclamation. Part of which read as follows: "I, J.M. Stone, governor of the State of Mississippi, do recommend that on Friday, the 30th day of September, all Christian people throughout the State repair to their respective places of worship and offer up their united petition in prayer to God, that He will withdraw from our people this terrible affliction, and that He, in His infinite goodness and mercy, will restore them to health and bring peace to their mourning households".

Since the yellow fever quarantine had shut off the people of Ocean Springs from the outside world, conditions were very difficult. The Ocean Springs Relief Society was formed in early September 1878, to assist those in need. H.H. Minor Sr. (1837-1884) was president, R.A. Van Cleave (1840-1908)-treasurer, and J.M. Ames, secretary. The society collected $767.25 with the Howard Association of New Orleans, the citizens of Galveston, Texas, and the Moss Point Relief Committee being the largest contributors.

The L&N creosote plant at West Pascagoula (Gautier) sent ten barrels of creosote free of charge to be distributed among the populace. It is believed the creosote was burned to "purify the air".

Several letters referring to the 1878 yellow fever epidemic survive and shed some light on this perilous event at Ocean Springs. Dr. Don Carlos Case (1819-1886), a native of Albany, New York, practiced medicine at Ocean Springs from sometimes after the Civil War until his demise in 1886. In 1881, the Case family built a large neoColonial style home on the southwest corner of Washington and Porter. The Case heirs sold it to H.F. Russell (1858-1940) in 1905. The Russell home was damaged in February 1933 conflagration and later removed.

Dr. Don Carlos Case wrote the following letter in August 1878, describing yellow fever conditions at Ocean Springs:

Ocean Springs August 25, 1878

To the Editors of the Picayune:

It has been a matter of much interest with some, and great solicitude with many, to know the true and exact situation as to the health and sanitary conditions of this Gulf Coast. I have seen in your paper communications from Bay St. Louis, Mississippi City, and Biloxi giving assurances of the good health and entire exemption from yellow fever of those places, and I deem it my duty to make known the true situation at this place.

We have had one death from yellow fever at this place, that of Colonel Strout of the Hotel (refers to the Ocean Springs Hotel). He was my patient from the first and I was with him to the death. He died on the third day of black vomit.

He was a Northern man, only two and a half years in the South; never had any acclimating sickness, and was otherwise a highly susceptible subject, laboring as he did under organic disease of the kidneys. Being the principal outside manager of the Hotel, he was unavoidably and constantly brought in contact with persons, goods an mail matter arriving daily from the city (New Orleans).

Only one other case, a lady guest at the Hotel, has had fever, but she has fully recovered. This lady was taken with the fever simultaneously with Colonel Strout, and consequently must have contracted the disease in a similar way.

Not another case has occurred up to this time, and no symptoms of any, neither at the Hotel nor in any part of town.

Mrs. Huntington, the lady matron of the Hotel, and her young and amiable daughter, but recently from the North and wholly unacclimated, were the principle ones to nurse and take care of Colonel Strout during his sickness and death; yet neither of them contracted the disease.

I mention this circumstance more particularly to show how little or likely the disease is spread in the pure and invigorating atmosphere of the Gulf Coast. The Hotel has been thoroughly fumigated and cleaned, and is now in as healthy condition, and as free from all contaminating influences as it ever was. The town is in a most perfect sanitary condition. No sickness nor no cause of sickness.

No fears are entertained of any spread of the fever at this place and we extend to our friends in the city (refers to New Orleans) acordial greeting, that they may come here with perfect safety, and enjoy the pure wholesome atmosphere of this Gulf Coast, and thereby escape the foul and pestilent atmospheric conditions of the city.

Very truly yours, D.C. Case, M.D.

EPILOGUE

Additional research on this subject has uncovered some interesting side lights to this letter of Dr. Case. A series of approximately forty letters written from August 2, 1878 until September 15, 1878, from Mary Plummer Buford (1808-1878) at Ocean Springs to her husband Albert G. Buford (1813-1878+) of Water Valley, Yalobusha County, Mississippi, relate some of the events of the 1878 Yellow Fever Epidemic. The Buford letters are now in the possession of Wally Northway, a descendant of A.G. Buford. Northway is a resident of Florence, Mississippi.

Mary Plummer Buford, nee Porter?, had acquired through the years, property at Ocean Springs with her deceased husband, Joseph R. Plummer (1804-1872+). Present day Plummer Point on which the Ocean Springs Yacht Club is located was named for this individual. In August 1878, Mrs. Buford came by train from Water Valley in north Mississippi to Biloxi via New Orleans and then by boat to Ocean Springs. The sea journey was necessitated because of a yellow fever quarantine. The city of New Orleans had been declared an infected port by the Jackson County Board of Health. Their decree stated that:

"no railroad train, car or engine shall, after the 29th day of July (1878), stop within the limits of Jackson County when coming from said city of New Orleans, under penalty of law, but shall be allowed to travel at a rate of speed not less than ten miles an hour when delivering mails, and all vessels coming from New Orleans shall wait the quarantine physician outside of the bar at the mouth of the Pascagoula River. When coming into Ocean Springs one shall stop at he county line, one mile below the railroad bridge, about opposite the old Egan wharf, and shall then be subject to the orders of the quarantine physician at the respective places, and no person shall come into the county of Jackson who has been in the city of New Orleans within the last ten days pending their arrival in said county".

Mrs. Buford was attempting to ascertain the condition of her property in the Gulf Hills area known then as the Oak Lawn Place. She stayed at the home of Mrs. Tobias on Washington Avenue opposite the Shanahan House. While on this mission, she contracted the dreaded "yellow jack" and died at Ocean Springs on September 11, 1878. Before her demise, Mrs. Buford also recorded the death of Colonel Strout of the Ocean Springs Hotel. On August 19, 1878, she wrote to her husband at Water Valley: Mr. Strout one of the proprietors of the hotel died last night, and Dr. Dunlop (sic) dispatched the board of health this morning...that he died of black vomit and the place is in ferment. The citizens have protested against his remains being carried through town and he will be buried in the hotel yard.

As regards the Huntingtons at the Ocean Springs Hotel, Mrs. Buford wrote on September 2, 1878:

I am quite well and trust in God that I may escape the dreaded fever that is growing fast upon us. There is another case at Shanahan's were the priest (Father Charles Van Quekelberge) is sick. Miss Huntington died this morning. Mrs. Huntington was taken down last night and her son is very low. I doubt not that the fever will attack all here who are unacclimated. It has a long time to run yet. I am hopeful as to my acclimation which is in a fair way to be tested. Mrs. Tobias and Mary Perin visit the sick at Shanahan's, and the priest is very ill and Mary says he is very yellow, so I am then liable to take it at any time, if not acclimated. I have used disinfectants the best I could, but time will show.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star reported in September 1878, that John and Mrs. Huntington were ill at the hotel of yellow fever. Her eighteen-year old daughter, Alice Huntington, a native of Cleveland, Ohio died of the fever on September 2, 1878. Mrs. Huntington and her son, John, must have survived the fever as they were reported leaving for Ohio in early November 1879.

Other known to be ill in the village were: Three from the Maginnis family; Mr. Blackburn; Mrs. Johnson; Mrs. Julia Egan (1833-1907) and her two sons; Dr. J.J. Harry (1854-1950), two daughters of Mrs. Shanahan, and Miss Ida Delavallade (1862-1878+), the granddaughter of Belle Tiffin (1824-1900) of New Orleans.

Dr. Jason J. Harry, a native of Hale County, Alabama, had just received his medical degree from Tulane when he came to Ocean Springs. Dr. Harry was in charge of the yellow fever quarantine here. The local reporter for the Pascagoula Democrat-Star related on October 4th that, "Dr. Harry is still true and heroic in the cause, and his efforts have been crowned with success, as almost alone he stands. Being young and unacclimated we fear he will fail". Dr. Harry recovered and moved to Handsboro where he replaced Dr. John Lyon who expired of the yellow fever.

There were approximately one hundred seventy-five cases of yellow fever recorded at Ocean Springs from the nearly six hundred people believed to have been here at the time. From this population about thirty deaths were recorded. Many were small children. Known victims of this scourge in 1878 at Ocean Springs are:

Colonel Fredrick H. Strout (1840-1878)-manager of the Ocean Springs Hotel and a native of Androscoggin County, Maine, died August 18, 1878. Buried in the Ocean Springs Hotel Cemetery.

Alice Huntington (1860-1878)-daughter of James and Matilda T. Huntington of Cleveland, Ohio. She died on September 2, 1878. Miss Huntington was a member of the Methodist Sunday School and one of the brightest pupils in the bible class. She was probably buried at the Ocean Springs Hotel Cemetery.

Miss Matthewson (d. 1878)-no information probably died September 2, 1878.

Mary Helen O'Keefe (1863-1878)-daughter of Edward O'Keefe (1815-1874) and Mary Tracy (1832-1895). She died on September 5, 1878. Miss O'Keefe is probably buried at the Evergreen Cemetery.

Mrs. R.A. Thomas (1815-1878)-wife of B. Thomas. She may not have been a victim of the fever, but did die on September 7, 1878. No further information.

Father Charles Louis Van Quekelberge (1835-1878)-pastor of the Catholic Church at Pascagoula and a native of Ecloo, Belgium. He died on September 10, 1878, and his remains were interred at the Evergreen Cemetery. In 1869, Father Van Quekelberge advised Bishop Elder to build a new church at Ocean Springs. This resulted in the church relocating from Porter to a new structure on Jackson Avenue in February 1874. It is believed that Van Quekelberge came to Ocean Springs from Pascagoula to assist Father Meerschaert in comforting the ill and assisting at burials until he was striken with the fever. He died at the home of Irish immigrant carpenter, John J. Shanahan (1810-1892). The Shanahan home was located on the northwest corner of Washington and Calhoun.

Joseph Ryan (1840-1878)-son of Jerome Ryan (1793-1870+) and Marie Euphrosine LaFontaine (1802-circa 1846). Ryan expired on September 15, 1878. His remains were probably buried at the Bellande Cemetery.

Mrs. Denison (d. 1878)-no information. Died September 21, 1878.

Mr. Kimbrough-(d. 1878)-no information. Died September 1878.

Two children of W.S. Brown-no information. Died September 1878.

Two and possibly three children of Mrs. James (a visitor)-no information. Died October 1878.

Charles W. Eason (1849-1878)-a native of Westfield, New York died on October 12, 1878. Probably the last victim of the 1878 Epidemic at Ocean Springs.

A journalist reporting from Ocean Springs for The Pascagoula Democrat-Star on October 28, 1878, had this to say about the 1878 Yellow Fever Epidemic: "when poets write and journalist tell the sad tale of 1878, upon the page in black and white Ocean Springs will be seen, but to heaven cast an eye, 'Amen', not the first neither the last in the mention of epidemics. When to the graveyard on our annual procession let someone plant a flower and breathe a prayer over the newly made graves of the strangers that with us met the dark lot fate had in store for us".

THE 1897 YELLOW FEVER EPIDEMIC

The 1897 Yellow Fever Epidemic started at Ocean Springs in August. It was initially believed that the more than five hundred cases at Ocean Springs were dengue fever and that it had originated at Ship Island. Dr. Olliphant, president of the Louisiana Board of Health, in his official report declared the contagion as a mild type of dengue fever. His declaration was later reinforced by Colonel R.A. VanCleave (1840-1908) who was quoted by The Pascagoula Democrat-Star on September 17, 1897, as follows: I have been through the yellow fever epidemics of 1875 and 1878 and according to my experience and observation, no yellow fever exists or has exited in Ocean Springs.

Later in September, yellow fever was diagnosed and New Orleans and the rest of the South quarantined Ocean Springs. Unfortunately hundreds of excursionist had already returned to New Orleans and the pestilence soon spread to cities in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, Texas, and Kentucky. The final records for the 1897 episode indicate that nearly 500 deaths occurred from the 4000 cases of fever reported. New Orleans accounted for 300 deaths.

At Ocean Springs, it is believed that three people died from yellow fever. Dr. J.H. Bemiss (1855-1897) of New Orleans who came from New Orleans to assist the over worked Ocean Springs medicine men died from the black vomit. It is interesting to note that Dr. O.L. Bailey (1870-1938), who was in the thick of the epidemic at Ocean Springs, had a son born on June 29, 1898. He was christened Bemiss O. Bailey. The other fever deaths are believed to have been a Miss P.E. Schultze and a Mr. William Seymour, Jr.

On November 19, 1897, The Pascagoula Democrat-Star in a summary of the deaths that occurred during the crisis at Ocean Springs reported the following who died during this period: August 1897-William Siegerson, Mrs. Saunders, Mary Murphy (1807-1897), Susan A. Berry (1848-1897), Fearn Egan, Lula Alfriend, T.A.E. Holcomb (1831-1897), and Jennie Dillon. September 1897- Dr. J.H. Bemiss (1855-1897), John T. Tillman, Sarah Johnson (Black), P.E. Schultze, William Seymour Jr., W.S. Bransford, O.W. Elan, Mattie Goodrich, and Mrs. Ida L. Cubbage (1870-1897).

Captain Antoine V. Bellande (1829-1918) was appointed the official fumigator. Men under his supervision disinfected and fumigated places where deaths had occurred. Bellande worked as a bar pilot at Ship Island and had been exposed to yellow fever and quarantines there for decades.

It was never ascertained with a high degree of certitude the source of the initial yellow fever case at Ocean Springs. It was initially thought that a traveler from Guatemala was the culprit, but later opinion established the probability that the scourge was brought here by Cuban rebels who operated out of Ocean Springs at this time.

Camp Fontainebleau

At Jackson County, two facilities were established for quarantine purposes. A detention camp, called "Camp Fountainbleau", was built nine miles east of Ocean Springs, and the Round Island Quarantine Station off Pascagoula was designated a place to receive refugees arriving from infected places. "Camp Fontainebleau" was established by the United States Marine Hospital Service transferring from Waynesville, Georgia. Soldiers guarded the six hundred refugees in the camp which had two areas-one for treating yellow fever cases lead by Dr. Gaines and the other for those suspected of having the disease which was in charge of Dr. Giddings.

Although never used again, a "Camp Fontainebleau" remained until the last lumber was sold in 1916. The buildings were sold and the equipment was shipped to other camps as needed. A.V. Sceals (1859-1916), the custodian, who transferred from Georgia, kept this position until all of the medical equipment was removed. Sceals, a native of Edgefield, South Carolina, was a building contractor and later construction foreman for the L. & W. R.R. He formerly lived at Brunswick and Atkinson, Georgia before he entered the U.S. Marine Hospital Service at Waynesville, Georgia. Children: Robert W. Sceals, James Edwards Sceals, Mrs. J.M. King, Mrs. W.T. Lacy, and Avis Beulah S. Walker (1898-1946).

A.V. Sceals remained in the area as a farmer at Fountainbleau and lived at mile from the depot. Daughter, Avis Beulah Sceals (1898-1946), married Abel V. Walker. Died in mid-April 1946, at Norco, Louisiana.(The Daily Herald, April 16, 1946, p. 2)

REFERENCES:

Khaled J. Bloom, The Mississippi Valley's Great Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878, (LSU Press: Baton Rouge, Louisiana-1993), pp. 280-281.

Margaret Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South, (Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, New Jersey-1992), pp. 136-137.

John W. Scott, Journal of Mississippi History, "Yellow Fever Strikes Bay St. Louis: The Epidemic of 1897", Vol. LXIII, No. 2, Summer2001.

Source Material for Mississippi History, Jackson County, WPA Historical Project-1939, pp. 419-420.

Mississippi Coast History and Genealogical Society, Volume 9, No. 4, "A Short History of Saint Alphonsus Parish, Ocean Springs",November 1973, pp. 132-133.

Journals

The Daily Herald, "The Mississippi Coast and Yellow Fever", March 1, 1936.

The Ocean Springs News, "Body of A.V. Sceals Found---No Foul play. Death by Nat'l Causes", February 10, 1916, p. 1.

The Ocean Springs News, "A.V. Sceals Obit", February 17, 1916, p. 4.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs Items", August 23, 1878, p. 3.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Died-Alice Huntington", September 13, 1878, p. 2.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Governor Stones Proclamation", September 20, 1878, p. 2.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "In Memoriam-Mrs. R.A. Thomas and Mary Helen Keith", September 20, 1878, p. 2.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "From Ocean Springs", September 27, 1878, p. 3.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs", October 4, 1878, p. 2.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs", October 18, 1878, p. 2.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Died-C.W. Eason", October 18, 1878, p. 2.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs", October 28, 1878, p. 2.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Report of the Ocean Springs Relief Society", December 20, 1878, p. 2.

The Sea Coast Echo, September 11, 1897.

LOCAL HURRICANES

September 23-24, 1722

August 10-12, 1860

September 14-15, 1860

October 2, 1893

August 15, 1901

September 26-27, 1906

September 20-21, 1909

September 29, 1915

July 5, 1916

September 20-21, 1926

September 3-4, 1947

September 9-10, 1965 (BETSY)

August 17, 1969 (CAMILLE)

September 12, 1979 (FREDERIC)

September 1-2, 1985 (ELENA)

September 30, 1998 (GEORGES)

September 16, 2004 (IVAN)

August 29, 2005 (KATRINA)

THE 1893 HURRICANE: THE GREAT OCTOBER STORM

The 1893 Hurricane, referred to by historians as the Great October Storm or the Cheniere Caminada Storm, struck the Mississippi coast slightly west of the Alabama state line on the morning of October 2, 1893. Winds in excess of 100 mph and rainfalls of up to eight inches were recorded at many coastal towns. The highest official storm surge reported in Mississippi was 9.3 feet at Deer Island where forty cattle were drowned and their carcasses deposited at the Biloxi lighthouse along with timbers of boats, saloons, oyster houses and piers.

On October 1, 1893, the tempest first struck the coast of southeast Louisiana. Here winds in excess of 130 mph and a storm surge of 15 feet generated from the waters of Barataria Bay and Caminada Bay drowned 1,650 people from the population of 1,800 persons living on Cheniere Caminada, a small fishing community, near Grand Isle.

On October 1-3, 1993, the "Cheniere Hurricane Centennial" was observed at Cut Off in Lafourche Parish, Louisiana. The weekend was a combined memorial to victims and survivors of the 1893 disaster and a reunion of their descendants. In addition, demonstrations of ethnic cooking, music, dancing, and life of the bayou country were presented. Story telling, environmental programs, genealogical workshops, art, and photography added to the cultural and educational experience of the remembrance.

After exiting Caminada Bay, the Great October Storm moved rapidly northeast inflicting heavy damage to the fishing fleet working the fecund waters of the east Louisiana marshes northwest of Breton Sound. It is estimated that hundreds of sailors died here from drowning during the tempest or from exposure during the days following the aftermath of the storm. Along the turbulent path to its Mississippi landfall, the Great October Storm destroyed the U.S. Marine Hospital, Quarantine Station, and lighthouse at Chandeleur Island.

Washington Avenue

[Courtesy of Adrienne Illing Finney]

Local damage

Regrettably for the beachfront inhabitants at Ocean Springs who remembered the gale of mid-August 1888, the approaching hurricane would soon make them forget that blow. The damage in 1888 generally amounted to lost piers, bathhouses, breakwaters, and some trees. The Daily Picayune of August 24, 1888, reported destruction to the wharves and bath houses of: The Ocean Springs Hotel, Mrs. Julia Ward, Mrs. Julia Egan, John Cunningham, Mrs. Illing, Mr. Hemard, Bishop Keener, Reverend Dr. Joseph B. Walker, and Ralph Beltram. The grand lawn of the Arthur Ambrose Maginnis Jr. estate, west of the W.B. Schmidt estate, was strewn with fallen trees. Schmidt lost a portion of his breakwater. Narcisse Seymour, who operated a fish house and saloon at the foot of Washington Avenue, lost both during the high tides and wind of the raging blow. (The Daily Picayune, August 22, 1888, p. 2)

The Gillum Hotel (originally the Van Cleave Hotel) located on the southeast corner of Washington Avenue and Robinson Avenue, opposite the L&N depot, was badly shaken by the heavy winds. It had to be repainted. Mrs. Adele H. Gillum gave up her lease on the hostel, which was owned at the time by Mrs. Emma Arndt Meyer (1866-1924+). Gillum and her daughter, Effie, moved to New Orleans in January 1894.(The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, October 6, 1893, p. 2)

L&N Railroad Bridge

[Courtesy of Adrienne Illing Finney]

The L&N Railroad

First reports of the 1893 Hurricane destruction at Ocean Springs indicated that the most severe devastation occurred when the L&N Railroad bridge across the Bay of Biloxi was washed away. Hurricane force winds drove a 200-foot section of the structure into the Back Bay of Biloxi. The floundering rail span wreaked havoc on boats, wharves, and seafood plants on the shore of the bay along the Biloxi peninsula. Mr. Jack Sheppard, the bridge tender's assistant, was drowned.

Rail passengers were delayed at Ocean Springs for several days until other arrangements for their travel could be effected. The corpse of Junius Hart, which was being shipped from New York to New Orleans, was on the train. It took several hundred men and over two weeks of intense labor to get the railroad bridge back into service. In addition, many boats and fences were damaged at Ocean Springs. When the first train reached Ocean Springs from Mobile on October 11th, it carried sixty bridge repairmen. The townspeople were furious with the L&N for not carrying their mail. The local postmaster had to row to Biloxi in a skiff to get the mail. Although four schooners and several steamboats landed at Ocean Springs via New Orleans, their captains had been denied access to the town’s mail.(The Biloxi Herald, October 21, 1893, p. 4)

Martime victims

The town became very concerned when the Alphonsine, a fishing schooner, commanded by Captain Paul Cox was overdue. The vessel had been shrimping in the Louisiana Marsh. The people of Ocean Springs and others of the coast were relieved on October 13, when Father Aloise Van Waesberghe of St. Alphonsus reported to the editor of The Pascagoula Democrat-Star that Paul Cox (1867-1942), Ed Mon (1843-1920), Van Court, and Ladnier have returned to Ocean Springs from Breton Island where they spent the days following the hurricane. The men survived on two croakers a day while they dug their beached schooner, Alphonsine, out of its quartz trap.

The Rubio brothers, Paul Fergonis (1861-1893) and Frank Fergonis (1865-1893), also known as Guiatan (Cajetan) or probably Gaetano brothers, of the Bayou Puerto settlement, were fishing in the Louisiana marshes aboard the schooner, Young America, and were caught by the hurricane. The tempest dismasted their vessel and drove it aground at Southwest Pass. Both men were lost at sea.(The Biloxi Herald, October 7, 1893, p. 1)

Accomplished Mississippi historian, Professor Charles L. Sullivan, in his excellent book, Hurricanes of the Mississippi Gulf Coast(1717 to Present), presents a descriptive account of a Biloxi schooner, which returned from the islands and marshes in search survivors: It is impossible to describe the horrifying sights witnessed on the voyage. The marshes are filled with dead and putrefying bodies, and in but a few cases are the corpses recognizable, and then only from the garments worn or some peculiar and well-known mark of distinction. In many cases the skin from the bodies had fallen off and the stench from the putrid corpses was so fearful that carbolic acid had to be used in all cases before attempting to handle a body, and sponges saturated with camphor and whiskey were applied to the nostrils of the relief party. All over the island were seen crosses, indicating the resting spot of some poor unfortunate who had given up his life to the cruel waves. The number of lives lost in the marshes will never be known, and doubtless many who perished and drifted out to sea. All over the marshes and in the water thousands of dead animals and water fowl were seen.(The Biloxi Herald)

Succor

The charity and concern of the town's citizens was expressed in late October, as the Ocean Springs Cornet Band gave a benefit concert at the Firemen's Hall for the relief of those who suffered financial loss from the tempest. The event was well patronized and considered a success. The Cyclone string band assisted at the performance and was well received by the audience. Laud was graciously given to the ladies who assisted with the arrangements and refreshments. The affair raised $65 for the victims of the storm.

Later repairs

About the same time, Dr. Edmond A. Murphy arrived from New Orleans to have his property repaired, which was damaged by the storm. In April 1891, he had purchased the Bay front estate south of the L&N Railroad from the Reverend Joseph B. Walker (1817-1897). Walker was a Methodist minister born at Washington D.C. Dr. Walker preached at the Carondelet Street Methodist Church at New Orleans until he retired to his summer home at Ocean Springs circa 1875. Reverend Walker was described as " a preacher of real power, his services to the Ocean Springs church, freely given, were of the highest order". Reverend Walker later relocated to his country estate north of Gulfport.

By late November 1893, repairs were still occurring along the shore face as The Pascagoula Democrat-Star related that Joseph S. Catchot (1856-1919) had recovered from a long illness and was rebuilding his wharf and oyster shop at the foot of Jackson Avenue.

Ocean Springs recovered from The Great October Storm as it had from its predecessors that had been recorded in the area by French colonists as early as 1717. Over two thousand people lost their lives in this October 1893 tropical cyclone. At least one hundred of these casualties were Mississippians. This hurricane ranks second in loss of lives caused by natural disasters. Only the Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900, which claimed more than 6,000 lives exceeded The Great October Storm.

We can be thankful today that we have the communications, satellites, and meteorological technology for early warning to these powerful natural forces. For those of us who experienced the 1947 September Storm, Betsy, Camille, et al, anxiety and empathy are emotions which surface easily when we hear or read about hurricanes. May all tropical waves from the east African coast meet their demise in the cool waters of the North Atlantic Ocean.

REFERENCES:

Ray L. Bellande, Ocean Springs Hotels and Tourists Homes, (Bellande: Ocean Springs, Mississippi), P. 54.

Charles L. Sullivan, Hurricanes of the Mississippi Gulf Coast 1717 to Present, (Gulf Publishing Company: Biloxi, Mississippi), pp. 30-40.

Robert B. Looper, The Cheniere Caminada Story, (Blue Heron Press: Thibodaux, Louisiana-1993, p. 1.

Journals

The Biloxi Herald, “The First Train at Ocean Springs”, October 21, 1893.

The Biloxi Herald, “Storm Victims”, October 28, 1893.

The Biloxi Herald, "J.B. Walker Obit", February 27, 1897, p. 1.

The Biloxi Herald, "Dr. Walker's Funeral", March 6, 1897, p. 4.

The Daily Picayune, "Correspondence", August 22, 1888, p. 2.

The Ocean Springs Record, "Sous Les Chenes", January 18, 1996.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs Local News", October 1893.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs Item", October 13, 1893.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, October 13, p. 3.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs Locals", October 27, 1893.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs Locals", November 3, 1893.

The Pascagoula Democrat-Star, "Ocean Springs Local News", November 24, 1893.

THE "EMMA HARVEY": A TALE OF THE JULY STORM, 1916

The recent near miss of Tropical Storm Alberto on July 3, 1994 reminded me of an incident that happened on the Mississippi Coast seventy-eight years ago almost to the day. It is a true story well documented in the journals and lives of the people of that time.

Ocean Springs

On the humid morning of July 6, 1916, railroad agent, John Drysdale (1869-1934), walked slowly across the L&N Railroad Bridge from Ocean Springs towards Biloxi. Soon he would announce to the world the fate of his little town on the eastern shore of the Bay of Biloxi. During the early morning hours a hurricane struck the Mississippi Coast roaring through Ocean Springs with wind gusts up to 125 mph. Destruction wrought by the tempest was manifested in roof, fence, chimney, tree, and shed damage.

No one was seriously injured, but plumber, George Dale (1872-1953), got a good scare when the Knights of Pythias Hall, which he was occupying during the storm got blown off its foundation. The colored Baptist Church was heavily hit by the strong wind force, and had to be torn down in the days following the storm.

In the country, the Rose Farm north of Fort Bayou reported severe damage. At the C.E. Pabst (1851-1920) pecan orchards some of the older trees were damaged. More fortunate was Theo Bechtel (1863-1931) reporting only slight ruin to his potential crop.

Biloxi

At Biloxi, L&N agent Drysdale found that city in great suffering. The hurricane had struck there also with unrelenting fury. The Back Bay and Point Cadet areas were especially hit hard. It would be days and even weeks before all the news of the great natural disaster would be known.

At the time many ships were operating in the Mississippi Sound. These vessels weren't outfitted with the communication and weather reporting devices we have today. Consequently, most of the sailors and their vessels were caught unprepared. Many of the Biloxi schooners were fortunate in that they were working near the partially sheltered Louisiana marshes. Other mariners sought haven in the lee of the offshore barrier islands. Those not so fortunate rode the storm out at sea. Most seamen made it home to their port. One small Biloxi schooner wasn't so fortunate.

It was the Emma Harvey and her story follows.

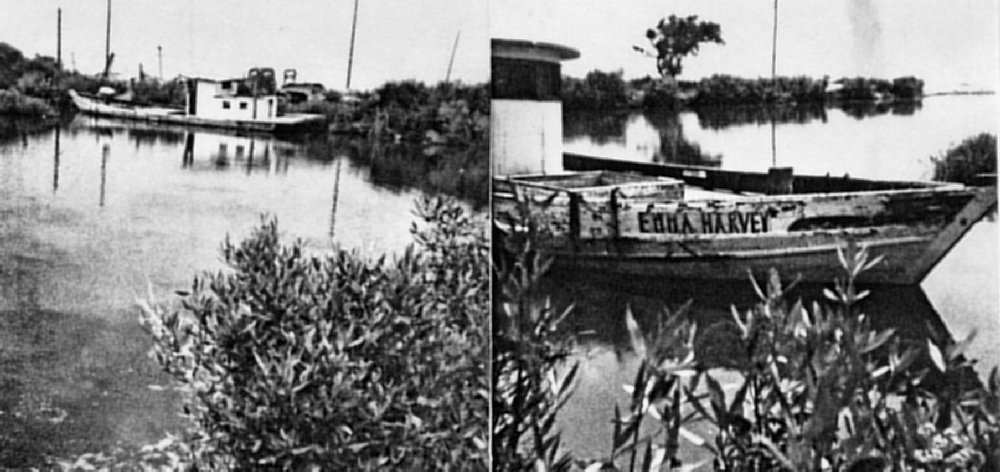

Emma Harvey

(final days and last known images of the Emma Harvey at Cedar Point, Alabama)

Emma Harvey

The Emma Harvey was a Biloxi schooner utilized in the shrimp and oyster industry of the Mississippi and Louisiana coasts in the early years of this century. She was built by Casimir J. Harvey (1845-1904) at his Back Bay, now D'Iberville, shipyard probably in the 1890's, and was named for his youngest daughter, Emma Agnes Harvey (1889-1968). Although the physical dimensions of the Emma Harvey are not known, it is documented in Chattel Book 2, p. 232 of the Chancery Clerk's Office of Harrison County that Casimir Harvey conveyed a schooner on May 25, 1889, to H.T. Howard. The boat was called the H.T. Howard, and was thirty six feet in length, fourteen and two sixteenth feet in breadth, three feet deep, and weighed eight and thirteen one hundredths tons.

The Emma Harvey participated in some of the early Biloxi schooner races. In the 1901 Biloxi Regatta, she withdrew before finishing the first round because of heavy seas. After the days of the White Winged Queens had passed, the Emma Harvey was converted to a charter boat and trawler. She was last seen about 1978 in a canal at Cedar Point, Alabama north of Dauphin Island. Every ship has a tale to tell. TheEmma Harvey has many and is an unusual craft as will be demonstrated.

On Tuesday morning, the Fourth of July 1916, the Emma Harvey owned by Ulysses (Lel) Desporte (1861-1927), a Biloxi oyster dealer, departed Back Bay on a shrimping trip to Chandeleur Island. Unknown to Captain George Duggan and his crew who consisted of Arthur Duggan, Lawrence Bennett, John Helm, John McDuffy, and Jack Atkinson, an Englishman, a category three hurricane was poised to strike the Mississippi Gulf Coast the following afternoon (July 5th).

The July Storm

The July Storm as it is known in the annals of Gulf Coast meteorology came ashore between Ocean Springs and Pascagoula, Mississippi. During this cyclone, several barometers in Biloxi registered 28.08" of mercury. Although this was the lowest barometric pressure ever recorded to this date, it was relatively high when compared to the mighty Camille of August 1969, which had a record low pressure for any storm to that time of 26.06" of mercury. The wind direction in the early hours of the storm was northeast, but shifted to the west where it remained until it abated in the early hours of the morning of July 6. A wind velocity of 90 miles/hour was recorded at Biloxi.

The Emma Harvey reached Chandeleur Island and was at anchor in Schooner Harbor on the west side of the island. This fact was corroborated by Captain Robert Williams of the schooner, Lagoda, also a victim of the furious storm. Other ships in the immediate area were the schooners: Laguna (Lagonia), and the Beulah D. The crews of these vessels were rescued in the days immediately following the hurricane by boats from Biloxi.

A vivid description of the harrowing experience in the Chandeleurs aboard the Beulah D is given by Louis Largilliere (1861-1950) inThe Daily Herald on the 10th of July, 1916, pp. 1 and 3. He stated: that he never wanted to go through such an experience again and he is grateful that he reached the mainland again. The Beulah D was caught in the storm while at anchor in Chandeleur Sound near North Keys. After the blow had overtaken them they put out two anchors but they were of no avail and the schooner was carried about the Gulf for a distance of thirty five miles after the masts had both blown out by the gale. During the drifting of the boat the members aboard were compelled to remain below most of the time as the wind was so strong that had they attempted to walk on deck they would have been blown overboard and lost forever. The hatches of the boat were blown away and canvas had to be tacked down to keep out the torrents of rain.

Search

In the days and weeks following the great blow, Lel Desporte sent out motor vessels, primarily the Ursula C, captained by Johnny Duggan or Boy Bennett. With other relatives of the missing crew, they made a complete search of Cat Island, the Chandeleurs, Cryhoe Bay, Point Comfort, Earl Island, Bird Island, Breton Island, Taylor's Pass, North Keys, Battle Door, Southwest keys, and Neptune, Louisiana. This valiant search of the western sector discovered the abandoned schooner, Segura, and the schooner barge, Hussler, both from Biloxi at Cryhoe Bay in the Louisiana marshes. At Taylor's Pass, they located a drowned fisherman.

The only physical sign of the Emma Harvey after the great storm in the Chandeleurs was reported by Captain G.L. Fields of the schooner, Beulah D, who stated that when his crew went ashore on the island to search for signs of the Emma Harvey, they found nothing but a small meat board and small pieces of rope that had drifted ashore from some boat during the gale. They could see in the sand where the Emma Harvey was believed to have dragged her two anchors in her journey across the island to the east during the blow.

By late July, the hunt for the missing schooner continued aboard the Ursula C now captaincy by Flood Lanius. Henry and Fred Duggan, son of Captain George Duggan, were also aboard. The search party now concentrated its relentless efforts to the east combing Horn, Petit Bois, Dauphin, and lesser islands in that area. They also went to Pascagoula, Mobile, and the west Florida coast seeking information and leads.

There were some sightings in the eastern Gulf, which gave hope for locating the missing crew and boat. The Coast Guard cutter,Tallapoosa, reported on July 11 that it had passed a schooner's mast twelve feet out of the water at Latitude 29.18 N and Longitude 86.55 W (approximately 100 miles southeast of Pensacola). About the same time, the private yacht, Shirin, of New Orleans passed a vessel within six miles of Grant's Pass (near Dauphin Island) with its right side up.

An unusual event occurred on August 2, when Martin Lomax, a teenage lad from Biloxi, found a bottle with a note in it on the south side of Deer Island. The note read: "Help. Help. On an unknown island". Signed George Duggan and crew. Some thought the note a hoax while others believed John Helm had written it since he always carried an empty flask in his pocket when at sea to be prepared for the emergency of a shipwreck.

Found

The destiny of the vanished Emma Harvey was discovered on August 12, when the lost schooner was located by two fishing boats from Pensacola. She was found floating bottom side up about twenty five miles from Pensacola (other reports point to a location of seventy five miles). No sign of captain Duggan or any members of his crew were ever found. The derelict was towed to a mooring point near the Perdido Wharf in Pensacola by the tug, William Flanders.

Mr. Bruce S. Weeks, Deputy Collector of Customs at Pensacola, stated in his report of the incident the following: There are absolutely no indications that the crew of the Emma Harvey was saved and he expressed the opinion that the men from Biloxi, who went to the Chandeleur Islands on July 5, were lost in the hurricane, which swept over the Gulf on that date. No indication of crew and there does not seem to be much probability that they ever got away in the boats. The crew evidently cut away the rigging on the starboard side, but failed to cut it on the lee side first, and apparently, the rigging went over the port side, hung and the vessel simply turned over. The anchors appear to have been out, but only a short length of chain.

The Biloxi schooner, Emma Harvey, was deemed worth saving by Captain Rocheblane of the towing vessel, William Flanders, but because of the great salvage and towing expense, Lel Desporte decided to dispose of her in Pensacola.

The precedent information was assimilated from The Daily Herald in the issues July 7, 1916 through August 29, 1916.

Frank J. Duggan

A personal perspective of the incident is given by Frank J. Duggan (1912-2000) who is the sole surviving son of the skipper of the Emma Harvey, George Duggan. Frank Duggan resides at 344 Fayard Street in Biloxi on the site that his family moved to circa 1905. Previously the Duggans lived at 747 Reynoir. As Frank Duggan was only four years of age when his father, George, brother, Arthur, and cousin, Lawrence Bennett drowned that stormy July 5th evening east of the Chandeleurs, it wasn't until years later at the dinner table or while drinking beer with his older brothers, Charlie and Fred Duggan, that he would hear the familial version of the Emma Harvey disaster. The following narrative is a summary of the tale of the Emma Harvey as told to me by Frank J. Duggan on December 17, 1990.

The voyage to Chandeleur commenced as a suggestion from Johhny McDuffy when he told George Duggan, "hey, Cap, they're slaughtering shrimp out there and getting redfish with them in the seine". Captain Duggan mustered his crew, but son, Fred had disappeared to parts unknown. When the anchor was weighed, Fred Duggan was replaced by his brother, Arthur, a newly wed. Arthur was eager to earn good wages for his new family situation.

Fred Duggan who had sailed on the Emma Harvey many times with his father never liked the little vessel, and thought it unsafe in rough weather. He referred to it as a "deathtrap" and admonished Charlie Duggan to never sail on her. Fred preferred the larger schooner, Cavalier, and could never understand his dad's love for the smaller boat. The tragedy of the July Storm of 1916 has remained with the Duggan Family through the years as one would expect from such a sudden loss of loved ones.

After the Emma Harvey was towed into Pensacola and salvaged, a Miami man bought it from salvagers. He had it towed to southern Florida, and refurbish it with a new cabin, engine, and trawls. The US Coast Guard became suspicious of the vessel since it never seemed to utilize it fishing gear. When they boarded the craft, a cargo of illicit Cuban spirits was discovered in the hole. The rum runner was confiscated and sold at a sealed bid auction in Miami as a victim of the Prohibition enforcement years (1919-1933). The purchaser, an Alabama man, returned the Emma Harvey to the Gulf Coast, probably to Bon Secour, Alabama.

Cedar Point, Alabama

A trip by the author, to Cedar Point and Dauphin Island, Alabama on December 31, 1990 resulted in telephone conservations with Sadie Mae Collier Serra and John Henry Lamey. Sadie Serra is the daughter of Frank Collier. According to her, Frank Collier obtained the Emma Harvey from a Bon Secour man in a trade. The man may have been John Steiner or Budgey Plash. Collier gave $800 worth of fine oysters for the vessel.

Mrs. Serra, the tenth of eleven Collier children, told of her father's success as a business man in Mobile County. Frank Collier and two associates owned twenty-five boats, a canning factory and grocery store on Dauphin Island, and an ice plant at Mobile. A disastrous fire at the ice plant and the Great Depression combined to bring the Colliers to financial chaos. They moved to Cedar Point circa 1933 with only 75 cents in the family treasury. Frank Collier began life anew by oystering in the bay. His wife opened the mollusks and sold them. This "mom and pop" operation

slowly grew, and the Collier children were integrated into the operation as their age allowed. Sadie Mae Serra said that the Collier fortunes improved rapidly after the Emma Harvey acquisition.

Initially, the old Biloxi schooner was put to work as a ferryboat transporting people, mail, automobiles, and cattle from Cedar Point to the island. The Colliers ran a herd on the west end of Dauphin Island.

Prior to World War II, the Emma Harvey would take day charters to the snapper banks. During the war years, fear of German submarines caused Captain Collier to ply the coastal and bay waters for trout. He would take as many as twenty people out for $30 per day and give them a delicious fish fry after the trip.

During the September 1947 Hurricane, the Emma Harvey was trapped by low tide at her mooring in the Cedar Point canal. The Collier family left for higher ground. When they returned the next morning, they found the valiant little lady on high ground adjacent to their store. During

the night of fierce winds and violent seas, the vessel had stood as a barrier to protect the Colliers' building from storm tossed flotsam and other debris.

John Henry Lamey, a neighbor to Sadie Mae Serra, at Alabama Port worked as a deckhand on the Emma Harvey in the 1940s and 1950s with Weldon "Doc" Collier, the brother of Sadie Serra. He vividly recalls the search and discovery of the wreckage of a National Airlines DC-6 airliner, which crashed into the Gulf about twelve miles south of Fort Morgan. The accident occurred in February 1953. The commercial aircraft was en route to Moissant Airport, now Louis Armstrong International, at New Orleans from Tampa when it went down as the result of turbulent weather.

After the Dauphin Island causeway was completed in the 1950s, the Emma Harvey plied the bay and Gulf waters as a shrimp trawler. According to the indigenous people of coastal Alabama, the high tides and strong winds of Hurricane Frederick on September 12, 1979, blew the Casmir Harvey built schooner into the wide expanses of the Mon Island marsh or Portersville Bay to the west of cedar Point. The fate or position of the Emma Harvey is presently unknown, but it is generally held that the Biloxi built schooner was destroyed by Hurricane Frederick.

Epilogue-Ocean Springs, Mississippi-July 7, 1994

Today I receive a telephone call from Bobbie Bond Helm who resides at 309 Live Oak, Ocean Springs, Mississippi. She tells me that her husband, Joseph O. Helm, Jr., is the nephew of John Henry Helm (1893-1916) who was a crew member of the Emma Harvey. Mrs. Helm further details the Helm Family relating that there were four Helm brothers and a sister: Conrad (1890-1914), Martin Helm (1891-1954), John Henry (1893-1916), Joseph O. Helm (1896-1968), and Rita Helm (b. 1898). Their father, John G. Helm (1867-1949), of German ancestry was born at New Orleans while their mother was Josephine Molero (1858-1914) of St. Bernard, Parish. The Moleros were from the Canary Islands. All the Helm men were born at New Orleans, and died at Biloxi, except John who was lost at sea east of the Chandeleurs on July 5, 1916.

Frank J. Duggan (1912-2000), the son of Captain George Duggan, the skipper of the ill-fated, Emma Harvey, resided at Biloxi and was married to Carrie Mae Voivedich (1913-2001). She spent her formative years at Ocean Springs. Mrs. Duggan's father, Nichcolas Voivedich, owned a store, on Washington Avenue about where Miner's Toys is now located. The Voivedich Brothers store closed in the mid-1920s.

To my present knowledge, other Ocean Springs residents with familial connections to the Emma Harvey through its builder, Casmir J. Harvey (1845-1904), are: former Ward IV alderman, Phil Harvey; Carroll Clifford, Jackson County Board of Supervisor from Gautier; and myself. Phil Harvey is as direct descendant of Pierre Harvey, Jr. (1841-1878) and Victoria Koehl (1850-1904). Clifford descends from the builder, Casmir Harvey and Rosina Husley (1852-1937), and I am a descendant of Marie Harvey (1840-1894), and Antoine Victor Bellande (1829-1918). Marie was the eldest child, of French immigrant, Pierre Harvey (probably Hervais or Herve) (1810-1880+), and Celestine Moran (1811-1883). Casmir, Pierre, Jr., and Marie Harvey, who were born at Back Bay (present day D'Iberville), were siblings.