- Printer-friendly version

- 411 views

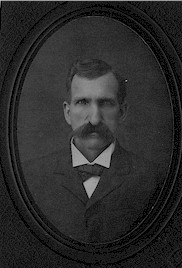

Emile Domning (1850-1918), the progenitor of the Domning family of Ocean Springs, was born in Germany on August 1, 1850. He immigrated to America in 1869 and in October 1878, became an American citizen at New Orleans. Domning served in the US Navy enlisting in 1873. In September 1880, he married Christina E. Sieckman (1848-1933), a native of Bielefeld, Germany, and the widow of John Wendel (1848-1874), in the Lutheran church in New Orleans. Christina was the daughter of Henry Conrad Sieckman and Anna Marie Ruter. In September 1867, she with two siblings, Johanna F. Sieckman who would marry Henry Wendel, and Christina Augusta Sieckman (d. 1875), immigrated to America settling with Ivan Sieckman, an uncle, residing at New Orleans.(The History of JXCO, Ms., 1989, p. 194)

Emile Domning (1850-1918)

In 1890, Emile Domning and family relocated from New Orleans to Ocean Springs. Here he made his livelihood as a shoemaker until his demise in November 1918. At Ocean Springs, Mr. Domning was active in the civic and social aspects of the community. He served Ocean Springs as marshal (sic), constable, and deputy sheriff.(The Jackson County Times, November 9, 1918, p. 5)

Acting Marshall

In March 1904, the Marshal elect of Ocean Springs resigned his post and Emile Domning acted as Marshal until a special election was held. During his short tenure as lawman of Ocean Springs, Mr. Domning met with a most embarrassing incident, which prevented him from seeking the office permanently. A rowdy group of young men were imbibing alcohol in the vicinity of the L&N Depot. Domning arrested one of the men and escorted him to the local calaboose with his mates in tow. Reaching the jail, Domning opened the door and entered the cell before his prisoner. Bam! Click! The jail door was slammed and sealed by the unruly crowd and left Marshal Domning as the incarceratee!! His prisoner and amigos escaped. Red-faced and angry, Emile Domning was later able to free himself.(The Progress, April 30, 1904, p. 4)

Domning children

Emile Domning and Christina Sieckman Domning were the parents of four children who were all natives of New Orleans: Augusta Domning Fayard (1881-1946), Benjamine F. Domning (1882-1915), Caroline M. Domning Seymour (1886-1969)and Amelia F. Domning Ryan (1889-1954).

Christina E. Sieckman Wendel Domning (1848-1933)

Bowen Avenue-a Domning neighborhood

It was several years after settling in Ocean Springs, that cobbler, Emile Domning, and spouse began to acquire land. In August 1892, Christina S. Domning acquired for $275, their homestead tract at present day 1314 Bowen Avenue. Situated on the south side of Bowen, it was described as Lot 5-Block 32 and purchased from Martha E. Ryan, John B. Ryan (1856-1920) and Ralph C. Bellman (1856-1899). A quitclaim deed was issued to the Domnings on this parcel by Samuel H. Dickin in July 1894. (JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk.14, p. 28 and Bk. 15, p. 588)

Emile Domning Home-Bowen Avenue (circa 1910)

[l-r: Ethel S. Endt Dale (1900-1978), Christina S. Domning (1848-1933), Johanna W. Endt ? (1873-1931), and Emile Domning (1850-1918)

By July 1918, several months before his demise in November 1918, Emile Domning possessed five houses on Bowen Avenue between Russell Avenue and General Pershing described as being in parts of Lot 3; all of Lot 4; Lot 7; and Lot 12 all in Block 32 of the 1854 Culmseig Map of Ocean Springs, Mississippi. He declared in his last will and testament that Christina, his spouse of thirty-eight years, would inherit his real property.(JXCO, Ms. Chancery Court Cause No. 4433-April 1924)

In April 1924, Christina S. Domning conveyed to her daughter, Amelia D. Ryan, “my homestead”. Amelia had married Fredrick J. Ryan (1886-1969) in January 1911.(JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 53, pp. 624-625)

In 1934, on the south side of Bowen Avenue in the front of their house Fred J. Ryan and Henry J. Endt (1910-1989) opened a neighborhood bar on Bowen Avenue. It was called the F & H Bar for their first names, Fred and Henry. This establishment soon evolved into a seafood restaurant and dancehall, which in June 1941 gained national notoriety when Mr. and Mrs. Ryan hosted William Meyers Colmer (1890-1980), Mississippi’s US Representative and Henry A. Wallace (1888-1965), vice-president of the United States. Their entourage included several leading Senators and Representatives from North Carolina, Kentucky, Alabama, Rhode Island, Virginia, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. (The Jackson County Times, May 5, 1934 and The Jackson County Times, June 8, 1941, p. 4)

The Fred Ryan home and businesses were demolished in the 1960s by their daughter, Esther Ryan Lyons Bradford (1919-1973), to build a new home. Her son, Fred R. Bradford, resides here today.

Emile Domning dies

Emile Domning expired at his Bowen Avenue residence on November 1, 1918, after an illness of several months. His corporal remains were interred in the Evergreen Cemetery. In early November 1918, The Jackson County Timeseulogized him as follows: The passing of E. Domning removes from our midst another of the old guard, who for years was prominently identified with Ocean Springs Fire Company No. 1. He was one of the few remaining veterans who in former years built up the fire company and worked year in and year out to keep the organization in a flourishing condition. He served many years as secretary of the company and was a faithful officer. (Ibid., November 9, 1918, p. 5)

Mrs. Domning passes

In early August 1933, Christina S. Domning passed on in her Bowen Avenue residence. Her funeral services were held at St. John’s Episcopal Church prior to internment in Evergreen Cemetery. Mrs. Domning was carried to her grave by six grandsons: Oscar Seymour and Bennie Seymour, Henry and Albert Endt, Emile Domning, and Ambrose Fayard.(The Daily Herald, August 5, 1933, p. 2)

A brief history of the children of Emile Doming and Christina Sieckman Domning follows:

Augusta C. Domning

Augusta Christina Doming (1881-1946) was born at New Orleans on August 10, 1881. She married Leonard J. Fayard Jr. (1881-1958), the son of Leonard Fayard (1847-1923) and Martha Jane Westbrook, (1851-1918), the daughter of John Westbrook (d. ca 1870) and Caroline Mathieu (1830-1895). Their children were: Ambrose Roch Fayard (1906-1998) married Lilly Mae VanCourt (1911-1998); Christine Fayard (b. ca 1910) married Clarence Hamilton (1902-1992); Lucille Fayard (b. ca 1916 married Oscar Heffner (b. 1923); and Beryl Fayard (1919-1972) married Willard J. Odenbeck (1918-1995) and Bernell S. Seymour (1922-1991).

The Fayard home-1302 Bowen Avenue

In March 1916, Emile Domning conveyed a part of Lot 3-Block 32 to his daughter, Augusta D. Fayard. This parcel on the southeast corner of Bowen Avenue and Russell had seventy-five feet fronting on Bowen Avenue and was one hundred fifty feet deep on Russell. The consideration was $75.(JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 42, p. 263)

Prior to residing here, the Fayards had lived on Bowen Avenue on Lot 7-Block 32. She acquired this parcel from her mother in June 1905, and sold it to her father in March 1916, for $75. Lot 7 was acquired by Johanna W. Endt (1873-1931) in April 1924, from her mother, Mrs. Emile Domning. The Endt-Hire cottage is situated at present day 1410 Bowen and owned by Theresa Hire.(JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 30, p. 53, Bk. 42, p. 380, and Bk. 53, p. 624)

Johanna W. Endt (1873-1931) was the daughter of John Wendel (1848-1874) and Chrisitine Sieckman Wendel Domning (1848-1933). She married Anthony J. Endt (1870-1948) in October 1896 at St. Alphonsus.(Lepre, 1991, p. 103)

In June 1960, after the deaths of Augusta D. Fayard and her spouse, Leonard J. Fayard Jr. in December 1946 and April 1958 respectively, three of their heirs conveyed the Fayard-Latch cottage to Bernell S. Seymour (1922-1991) and Beryl F. Odenbeck Seymour (1919-1972), a sibling and heir. After the death of Mr. Seymour in April 1991, his daughter, Suzanne Seymour Andrews of Titusville, Florida sold the old Fayard home place to Rickey L. Latch in late 1991.(JXCO, Ms. Chancery Court Cause No. P-3197-1991 and JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 985, p. 951 and Bk. 986, p. 130).

Benjamine Frederick Domning

Benjamine F. “Ben” Domning (1882-1915) was born at New Orleans in 1882. Circa 1904, he married Alphonsine Beaugez (1882-1965), the daughter of Alphonse Beaugez (1860-1942) and Caroline Seymour (1858-1933), in the St. Alphonsus Catholic Church at Ocean Springs. Their children were: Frederick Emile “Rip” Domning (1907-2005) married Maud M. Mugnier (1905-1998); Carrie Domning (1908-2000) who became Sister Mary Constance of the Pallotine Sisters, a Roman Catholic Holy Order; Bernard A. Domning (1912-1991) married Rita McGinnes (b. 1914); and Alice Domning Burnham (b. 1913) married Lawrence V. Burnham (1910-1988). Mr. Domning made his livelihood with the L&N Railroad.(Daryl P. Domning and Alice D. Burnham, July 7-8, 2003)

Domning cottage on Porter

It would appear that Ben and Alphonsine B. Domning initially made their home at Ocean Springs. They acquired Lot 12-Block 32 in early December 1904, from W.C. Parragin. This parcel fronted on East Porter near VanCleave and was due south of his parents’ home, which was situated at present day 1314 Bowen Avenue. Circa 1912, Ben was transferred to Mobile by the L&N. In December 1912, he sold his Porter Avenue real estate to his father. Two of the Domning children, Bernard and Alice, were born in Mobile.(JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 29, pp. 250-251 and Bk. 38, pp. 617-618 and Alice Domning Burnham, July 8, 2003)

Domning Cottage on VanCleave

Also in December 1912, Ben Domning acquired Lot 13-Block 33 (Culmseig Map-1854) on the east side of VanCleave Avenue from his father, Emile Domning. This lot had 100 feet on VanCleave and ran east for 190 feet. Here in 1913, he had a home erected which is extant at present day 504 VanCleave. Mr. Emile Domning had acquired Lot 13-Block 33 from Ellen L. Rapp in January 1912.(JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 37, p. 574)

Ben Domnings untimely demise

B.F. Domning was employed as a brakeman for the L&N Railroad in its New Orleans-Mobile Division. On March 18, 1915, while at work, he apparently fell from freight train No. 72 at Lake Catherine, which is situated about thirty miles east of New Orleans. B.F. Domning’s presence was missed when the fast freight reached Long Beach, Mississippi. His badly mangled corpse was found on the railroad tracks at Lake Catherine by the crew L&N train No. 88, which had embarked the Crescent City shortly after train No. 72. Mr. Domning’s corporal remains were brought to his parents’ home on Bowen Avenue before internment in the Evergreen Cemetery on Old Fort Bayou. He had been associated with several fraternal organizations: Woodmen of the World, Moose, and Firemen.(The Daily Herald, March 19, 1915, p. 1 and The Jackson County Times, March 25, 1915, p. 1)

On December 5, 1915, the Woodmen of the World unveiled a monument to B.F. Domning in the Evergreen Cemetery. Sixty-five members from Maple Camp No. 5 came from Mobile Several hundred people from Ocean Springs attended the ceremony.(The Ocean Springs News, December 9, 1915, p. 1)

Domning family members in Ocean Springs always believed that B.F. Domning was pushed from his L&N freight train by a hobo who was riding the rails to Mobile.(Clarence Hamilton Jr., June 25, 2003)

Settlement

In November 1915, the L&N Railroad paid the widow, Alphonsine B. Domning, and her four minor children $500 for the accidental death of her late husband. Contemporaneously, she was named legal guardian of her four children by the Chancery Court of Jackson County, Mississippi.(Jackson County, Ms. Chancery Court Cause No. 3475-November 1915)

Additional railroad accidents and deaths

Shortly after the demise of B.F. Domning, The Ocean Springs News reminded its readership that in addition to Mr. Domning, five other young men from Ocean Springs were seriously injured or killed in accidents on the L&N line. Among them were: Bennie Seymour, Elliot Westbrook, George Richards, Willie Westbrook, and Tom Eglin.(The Ocean Springs News, March 25, 1915, p. 2)

A brief review of these railroad incidents follows:

Benjamin Seymour

Benjamin “Benny” Benny Seymour (1882-1904), son of Narcisse Seymour (1849-1931) and Caroline V. Krohn (1847-1895), lost both legs below the knee at Bay St. Louis on December 17, 1904. Seymour was a flagman for the L&N Railroad. He died at Charity Hospital in New Orleans on December 18, 1904. Narcisse Seymour sued the L&N Railroad for $20,000 in a wrongful death suit and was awarded $5000 in damages by a jury in 1908. Judge Niles ordered the case retried and Seymour lost the suit in Federal court at Biloxi on February 16, 1909.(The Progress, December 24, 1904, p. 4 and The Ocean Springs News, February 20, 1909)

Elliot Westbrook

Elliot Westbrook (1883-1927), called Skinny, was the son of Lucian Westbrook (1842-1896) and Cecelia Kendall (1848-1913). Elliot was employed by the L&N at Mobile as a switchman. On October 24, 1910, he fell while attempting to make a switch of some cars in the L&N rail yard at Mobile. A car rolled over his right arm severing it near the shoulder. Westbrook resided at 459 Eslava Street, with his spouse.(The Ocean Springs News, October 29, 1910, p. 1)

George Richards

George Richards was employed by the L&N at Mobile. He worked as a switchman. On October 21, 1910, the bulkheads of two rail cars crushed his foot. The foot was amputated above the ankle by Dr. S.S. Peterson on October 25, 1910, when it did not heal properly.(The Ocean Springs News, October 29, 1910, p. 1)

William J. Westbrook

William J. “Willie” Westbrook (1886-1913) was killed in a railroad accident at Grand Bay, Alabama on February 23, 1913. While attempting to catch the caboose of a freight train, he lost his footing and fell beneath the rolling wheels of a freight car. Westbrook was the L&N station agent at the time of his demise. Willie Westbrook was the son of Edward M. Westbrook (1858-1913) and Harriet “Hattie” Clark (1857-1927). He probably had three children born in Alabama: W.J. Westbrook, Jr., Leroy Westbrook (b. 1908- pre 1980) and Lillian Westbrook (b. 1911). The two younger children lived at Ocean Springs with their grandmother, Hattie Westbrook, in 1920.(The Daily Herald, February 24, 1913, p. 1)

Thomas A. Eglin

Thomas A. Eglin (1887-1914) was the son of Albert M. Eglin (1852-1891) and Amelia S. Krohn (1855-1916). He was a flagman on L&N Train No. 38, better known as the New York Limited. Tom Eglin killed by bandits who robbed the conductor and baggage man for less than $20 on July 17, 1914. The armed robbery took place on the eastern outskirts of New Orleans. Eglin’s corporal remains were interred in the Bellande Cemetery at Ocean Springs.(The Ocean Springs News, July 18, 1914, p. 1)

Move to Mobile

In July 1925, Alphonsine B. Domning and her family relocated to Mobile, when her son, F. Emile “Rip” Domning (b. 1907), took a position with the L&N Railroad. The Domnings settled at 258 Jackson Street near Conception. In 1933, Carrie Domning joined the Pallotine Sisters at their convent in Huntington, West Virginia. The order had come from Germany in 1912, and in 1924, founded a hospital, which today is the St. Mary’s Medical Center, the 13th largest private employer in West Virginia. Bernard A. Domning became an electrician and married Rita McGinnes at Mobile circa 1935 and Alice Domning married Lawrence V. Burnham in August 1934, also at Mobile.(Alice D. Burnham, July 8, 2003)

Ocean Springs rentals

Alphonsine Domning maintained her properties on VanCleave while residing in Alabama. She rented the Domning cottage at 504 VanCleave until her demise in March 1965. Mrs. Domning’s corporal remains were interred in the Evergreen Cemetery.

In April 1933, during the Great Depression, Mrs. Domning lost her Ocean Springs home and lot for taxes to the State of Mississippi. She redeemed her property in February 1936, by paying $51.70 to the Land Commissioner of the State. A forfeited tax land patent was issued to her in September 1940 to clear the title.(St. Tax Land Sale Bk. 3, p. 142 and JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 77, p. 157)

In January 1974, Alphonsine B. Domning’s heirs, Emile, Carrie-Sister Mary Constance, and Bernard A. Domning Sr. sold her VanCleave Avenue properties to their sister, Alice D. Burnham and husband, Lawrence V. Burnham. A Chancery Court order was issued in March 1989, which adjudicated that all the real estate of Alphonsine B. Domning be assigned to her children.(JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 491, p. 574 and Jackson County, Ms. Chancery Court Cause No. P-2152, March 1989)

Today, Alice Domning Burnham of Mobile still possesses the old Ben Domning properties at 504, 506, and 508 VanCleave.

Reminiscences of Ocean Springs

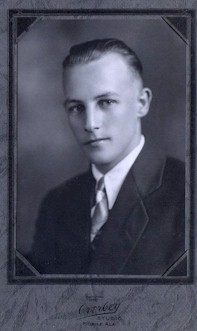

by Emile F. Domning

Emile Frederick “Rip” Domning (1907-2005), a native son, was born in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, on January 20, 1907, the eldest of the four children of B. F. Domning (1882-1915) and Alphonsine Frances Beaugez (1882-1965). Emile married Maud Marie Louise Mugnier (1905-1998), a native of New Orleans, but Biloxi resident on May 10, 1941, after which date they lived in Biloxi continuously except for Emile's World War II military service. Their only child, Daryl Paul Domning, was born in Biloxi on March 14, 1947. Rip Domning expired on May 21, 2005 at Burtonville, Maryland.(The Sun Herald, June 3, 2005, p. A7)

Emile F. “Rip” Domning (1907-2005)

Through his interest in Domning family lore and his father’s adventurous life before and during WW II, Daryl P. Domning who has resided in Silver Springs, Maryland since 1978, began to record Emile’s “reminiscences” on audiotape commencing in 1976. His present transcription of his father’s oral histories includes material recorded from the years 1984, 1987, 1995, 1998, 2000, 2001 and 2002.

Thank you Daryl for your contribution to our local chronology through this preservation effort. Daryl P. Domning, a Biloxian, who has made significant contributions in higher education and especially in the field of marine vertebrate paleontology, is a graduate of Notre Dame High School. Since 1978, after completing his formal education at Tulane and UC Berkeley, Dr. Domning has been an instructor in human anatomy in the medical college at Howard University in Washington D.C. He is a world authority on fossil sea cows, and his scientific investigation of these ancient marine vertebrate mammals has taken him to many parts of the planet. Daryl is well-published having authored or co-authored hundreds of papers and articles on the Order Sirenia.

School Days

When I was big enough to start school, we were living in Mobile; they used to bring me to school and come get me in the evening. I don't remember an awful lot about it, except that, like all kids, I didn't like it. But then, I didn't find the situation too tough; I was able to grasp the studies. When I started school I was about six or seven, and I was eight when my father got killed, so I didn't get very far. My mother decided to move back to Ocean Springs. The only thing I remember about my school days in Mobile was my teacher's name: Miss Young. She was just a girl teaching; it was probably the primer or something like that, just the beginning. We had coloring books, the usual things to start with. Of course, when we moved to Ocean Springs, that put me in a different school and I had to start all over again.

St. Alphonsus School

My mother was very much a churchwoman - she believed in her religion - and I hadn't been going to school long before a Catholic school opened up, and right away she pulled us out of public school and put us in Catholic school: now another start-over! So I wasn't getting anywhere. I think I was in about second grade at the Catholic school; but the congregation wasn't wealthy enough to support a school. There were a lot of people like my mother - hardly able to pay any tuition. Of course the school wasn't making it a big issue. My grandmother Domning, Christina S. Domning (1848-1933), had said they would buy my books and whatever was necessary, or pay whatever tuition was necessary, if I went to public school, because they were not Catholic. They were Lutheran, and my grandmother was very much against the Catholic Church. But my mother insisted that all her children be raised Catholic, and there was nothing my grandmother could do about it. She even proposed that the boys be raised in one church and the girls in the other, but my mother refused that too. So she and my grandmother didn't get along very well. But my mother said, "They are going to the Catholic school." So that was that; we went to Catholic school, and I don't regret that at all. They had three sisters that were teaching; they had a little old three-room house, and each one had a grade. How those poor sisters got along I'll never know, because the congregation just wasn't wealthy enough to support the school. So we went along like that and I had probably made about fifth or sixth grade, when the bishop or whoever was at the head of it closed the school down - they just couldn't afford it.

So now I'm out of school again, and going back to the public school! I was always in a brand-new school, so it never did take very well. Then, when I got to the eighth grade, on the first go-around the whole class, solid, failed. Now that's got to be the teacher's fault. I never heard of a whole class failing before. There was one boy, who we considered the teacher's pet, who did pass; the rest of the class failed. On the second go-around, another year, I was still in the eighth grade. I did pass; but that finished my schooling. I tried to take a couple of correspondence courses, but I still didn't have enough elementary education, enough foundation, to go ahead strictly on my own, with no teachers. By then, I was still fishing with my uncles, Henry Beaugez (1889-1963), Herbert Beaugez (1895-1954), and Mose Beaugez (1891-1973), not making anything, and I had quit the job; and by the time the school opened again in 1922 or 1923, I was carrying lumber as an employee of the Missouri Valley Bridge & Iron Company at the Rigolets east of New Orleans. We were building a railroad bridge for the L&N and I was clearing $17.50 a week plus room and board.

1900 public school

At the Ocean Springs public school*, we had a three-story school, but the third story wasn't used. It had four rooms, as I remember: two on the ground floor and two above. They were big rooms. At the time I started there, we didn't have any fire escapes. Later on, the powers that be said we had to have fire escapes. Actually, all the fire escape was a big old slide inside of a tube, like you see in any playground. They put these chutes up there, and we thought that was a great idea: we got a chance to go down the slide from upstairs all the way out! We used it anytime we could, until they put a door on it and could shut the door.

We used to have regular fire drills, and they would time us to see how long it would take us to empty a schoolroom. We were doing pretty good; they were praising us for always doing it just in the time we were supposed to. But one day they ran in a surprise drill on us, and we cut the time in half! We thought it was a real fire. Instead of being praised for it, we got chewed out about it, because we were pushing the persons ahead of us down and out of the chute.

For heat, each one of the schoolrooms got a pot-bellied stove. During the afternoon, they would let the fires go out, so they could set the fires [for the next day] with paper, kindling wood, and coal. All the janitor had to do [the next morning] was light the paper; then he'd take off for the next room. One day, after he had started his rounds setting the fires to warm it up for us kids, the whole building was enveloped with smoke. They decided that the building was on fire, and that was fine with us - we got the day off. But finally, when they investigated, they found out that some smart aleck had reached through the door on the stove and pushed a sack up in the stovepipe!

We had a fellow whose last name was Lemon**. He was sitting right close to the stove, so he could do this without being observed. He had a piece of iron rod that he could stick in the stove to get it hot, and then touch it to the floor to gradually burn a hole through the floor, to where you could look through the hole and see the pupils in the schoolroom below us. Me and a couple of my friends, we decided, well, now we got a hole in the floor; what are we going to do with it? We decided that when we would go out for recess sometime, we'd get a bottle and get some water and we'd smuggle the bottle in, and after things got settled down, we'd pour it through the hole. Well, the teacher of the class down below us sent word up to the teacher in our room that the water that we were using in the flowerpots was leaking onto the children downstairs. When she looked around the room, we didn't have any flowers! So they plugged the hole up!!

Our teacher's name was Miss Mabel Tardy (1897-1956+), who became Mrs. Mabel T. Johnson. She was sister to one of the smart alecks that I was running around with, Don Tardy (1907-1972). We were smarter than she was at least in our opinion. Miss Tardy might have been the teacher, but that didn't mean nothing. We knew all the best fishing holes. We knew everything we needed to know about hunting and things like that. Why would we want to go to school? The black kids didn't have any school; we thought they were luckier than we were.

Bell tower

Above the two floors that had the schoolrooms, they had a bell tower, and we had a big old bell with a rope hanging all the way down to the main floor to right behind the main door. You could pull that rope and ring the bell. You could hear the bell all over town, just about. We went up and looked the bell over one time, and we found out that the rope was tied about halfway around the bell, so that when you pulled it you would put the bell in motion. We found out that if you turned the bell upside down, the rope would be hanging straight, and you could yank on the rope all you wanted and you weren't going to do no good. Well, that didn't work for very long; they could send somebody up and push the bell over and get it in the right position and ring it. So then after some thought, we found out that you could wrap some sacks or anything around the clapper on the bell, and when it hit the side of the bell it wouldn't ring no how.

* Mr. Domning is describing the 1900 Ocean Springs Public School, which was situated on the southwest corner of Porter and Dewey. The large, wooden edifice was designed by D. Anderson Dickey of New Orleans and built by local contractor Frank De Bourg (1876-1954+). The school bell was donated in January 1900, by Herman John Nill (1863-1904), a native of New Orleans, who came to Ocean Springs in the late 1880s, with his family and opened a pharmacy on the northwest corner of Porter and Washington. With five children to educate, Mr. Nill had a vested interest in the quality of the local public school system.

An Ocean Springs Christmas

Ocean Springs was a very small town, and everybody knew each other. They told me that the only reason why anybody ever bothered to read the paper was to see who got caught! There were other things too to be considered, like Christmas. My Domning grandparents used to make eggnog. I don't know where they ever got that big bowl or whatever it was, but it would hold a good bit of eggnog. Nobody in town ever got any invitation or anything like that; but before the whole thing was over with, just about the whole town had been there anyway: they knew they were invited. I never did know the recipe for making this eggnog, but it was good stuff; it was powerful. Anybody who showed up around there usually got shook down - if they had any whiskey, it got confiscated and it got poured into the eggnog. Usually somebody would show up with a guitar, and they would get to drinking the eggnog and singing songs. Most of them were German; one - I can't remember the words to sing it - was "O Tannenbaum". Another was "Ach Du Lieber Augustin". That would go on and on and on until we ran out of eggnog; and everybody had all they could hold anyway before the party was actually over.

NOLA kinfolk

We used to have a lot of kinfolks in New Orleans. Back in those days the telephone communications between New Orleans and the surrounding towns were not very good, and I don't know why they didn't try writing; but along about the middle of the week, say on Wednesday, a keg of beer would show up. So that meant get the keg of beer on home, get it set up, start doing whatever cooking or making whatever other arrangements were necessary for the rest of that bunch of Germans to get over from New Orleans on the weekend. It was a good time; everybody had a good time. When they had the keg of beer set up, and it was ready to go, they used to have a little bucket or dish or something that they would set on the floor under the spout. We kids - myself, some of my first cousins - used to watch that, because when everybody came along to get them a little beer, some would drip down into this bowl or whatever they had down there, and when it got a little of the drippings in there, one of us kids would snitch it. That was our share!

The local fire company

We had a fire engine in Ocean Springs; they said they used to use it to hurry and get down to the fire so they'd have a place to sit down and watch the fire burn! Actually they had one, which was a hook-and-ladder deal. They had to tell me all this because I wasn't big enough to get in on any of this part of it; but all they had on it was a couple of long ladders. There was no such thing as a water system. So you'd get to a house that was burning, put the ladders up against it, and what were you going to do now? They had a bunch of buckets on there, but nobody had swimming pools in those days; actually the only water supply that they had were shallow wells that they had dug, and a few feet of water would seep into them, which was nothing but ground water. Then you had to get buckets with ropes on them. Then they got this pump, and could put a suction hose down in the well and then you could pump it out. With the first pump they had, they tell me (this is all hearsay), people would get on the side and pump up and down and pump the water. But the hook-and-ladder got burnt up in a fire. One of these wells that I knew of was right by the school, and I think they had two more somewhere else in town, but that was the only water supply for the firefighters, which was nothing. We used to have a big old barrel - the water would run off the house and into the barrel; and that barrel of water was in case the house caught fire. That was what you had to put it out with; that was your fire protection. Fortunately we never had to use it.

One Hallowe'en we went and stole the fire engine and hid it in an old stable, and then went and rang the fire bell. That was the only alarm they had, and that didn't tell you where the fire was. The engine was supposed to be pulled with horses, but they didn't have any horses either. It had big high wheels on it, so a bunch of us - Stanley Armstrong (1907-1979), Leroy Westbrook (1907-1989), I can't think of all of them - went and hid it and rang the fire bell. Of course everybody took off for the fire hall to get the engine. They got there and there wasn't any engine, so they figured somebody got there ahead of them and took it to the fire, and they were running all around everywhere trying to find the fire and there wasn't any fire. Finally somebody discovered the facts, and they swore and be damned that if they ever found out who did it they were going to hang them, but we kept our mouths shut!

Dances

We used to go to dances at the fire hall. The fire engine was kept in a long, narrow hall that opened on one side into the hall where they had the dances. To get rid of our hats, we'd hang them on the fire engine - we didn't have any place to check them, after all. Those hats were what we called a straw katy; that was just a cheap straw hat that everybody wore in the summer. It was only good for the summertime. If you wore them past a certain date, anybody that came along and knew anything about it would grab the brim and pull it down, and you'd be looking through the top of it! That's all it was good for, was that summer. The next summer you'd have to buy a new katy - they cost about a dollar or fifty cents, I don't know; they were very cheap.

One night, about the middle of a dance, somebody rang the fire bell, and the fire engine took off with all our hats, and they were scattered all over - we never did get our hats back. None of us had straw katies the rest of the summer; because they would get them in, you see, you'd buy them, and once they were sold out, they didn't get no more; that's all there was. So we didn't have no more fun pulling them down on people's ears. But we had a lot of fun at the dance.

That dance hall provided about the only public social gatherings we had. Sometimes boys would come over from Biloxi to go to the dance; maybe they had met some girls and wanted to meet them again. And then we'd always have a fight, and we'd run them back across the bridge. Now, when we went to Biloxi and went to a dance, we got run back across the bridge. There was nothing but the railroad bridge; there was no highway bridge like today.

The Big Fire

They did have one real bad fire in Ocean Springs. The wind was blowing strong and the fire was about to burn the whole town up. They even had to go as far away as Mobile to get engines to come in and try to help fight the fire. They ran a train out of Mobile with some of the old equipment on there, and from all around - Biloxi, Pascagoula, and everywhere - they were bringing in firefighting equipment, because that was a bad fire; it burned up a whole bunch of the town.*

Illings Theatre

Me and Don Tardy and Joe Green (who had lived in one of our houses one time) used to knock around together, and on the corner where the Baptist church is now, I think, Old Man Illing** had a theater - the town picture show. He had this big building right flat on the corner, which was like a house. But in the summertime it was too hot; people wouldn't go sit in there and watch the pictures. So he had a lot next door that he built a high board fence around, and called it the Airdome. There was no roof on it, just benches in there for when the weather was good. He had a son by the name of Bunny Illing***. Bunny used to run the projector. Me and Don Tardy and a couple others, we didn't have any money, and on Saturday evening when we wanted to go watch a Western show we'd go climb up in the oak trees and look over the top. Donald Tardy's father was the town marshal - he was the police force. He was sort of crippled in one leg. I don't believe he even had a pistol; if he did he wouldn't have known what to do with it. They'd start the picture - we didn't have any money to buy a ticket, even though I think the tickets were only about a nickel or a dime to get in. We'd get up in the tree, and Old Man Ed Tardy (1863-1943) - that was his name - he'd come along and he'd shine his flashlight up in the trees and say "Tum on down! Tum on down - I tee ya up dere" - he couldn't talk clearly - "Tum on down, I tee y'all up dere! Dona', I tee you up dere! I'm gonna beat your ass when you get home! I tee you up dere! I tee dat Domnin' boy too; I'm gonna tell his momma on him!" And that's the way it went. We wouldn't come down; we'd break little branches off and throw them at him. Because that's the only way we ever got to see the picture show; and there was nothing they could do about it.

But that picture show was really something. They'd get the reels in big round boxes, and put them in the projector, and then you had to turn the electricity on. The only electric wire they had in Ocean Springs was downtown, on the main street; out where we lived you used oil lamps. When you got the power on, you had to turn a crank so that you could pull the film from one reel to the other. Every now and then the tape would break - brrrrr! - and there'd be nothing on the screen. Then you had to sit there until Bunny was able to bring the two ends back together and glue them together again and go on with the picture. And that was the theater, the only one they had in town there. And that was usually the only way we got to see the pictures. I don't think it ever cost over 10 or 15 cents to get in; and sometimes maybe somebody might treat us, and we'd get to go inside on a free ticket. Oh boy, we were in high cotton now. All the boys around Ocean Springs wanted to sit in the very first row, right up against the screen. You'd be better off a few rows back, but we didn't want to fool with that; we wanted to be on the front row. After everybody got on there and somebody else would come along wanting to get on the front row too, there wasn't any room for him; so he'd get on there and push, and the other fellow on the other end would get pushed off. I imagine we were furnishing about as much amusement to the audience as anybody else.

Airdome

There was one thing about the theater that I guess you might say was comical. A lot of times in the summertime you'd have rain - a sudden shower would come up. While we were sitting in this Airdome that had no roof on it, so it would be cooler, a shower of rain would come up. Well, everybody would start dashing to get next door into the theater building, where it was hot. Of course, then it was up to Bunny Illing to get the projector and get it over there too and keep it dry, so all that took up time. That's when a lot of us kids would get in there too. In the rush we'd slip down out of the trees and go on in with them. Old Man Robert Rupp (1857-1930) was marshal then. He had taken Old Man Ed Tardy's place because Old Man Ed Tardy was a little bitty old fellow and crippled and one thing and another. Just about the time they got everybody into the theater - some of them were pretty wet by that time - and they were ready to crank up and show the picture inside, the rain would quit. Now they're going to move back outside. It took till pretty late sometimes to see all the picture!

* The Big Fire occurred on November 15, 1916. It commenced on the southeast corner of Washington and Porter where Mohler’s Service Station exists today and raced southward down Washington Avenue destroying on the east side of Washington Avenue, a store, home, and the fire hall of Ocean Springs Fire Company No.1. The west side of Washington Avenue saw the loss of two homes and the Vahle House, a small inn, situated on the northwest corner of Washington and Calhoun.

**Mr. Domning is referring to Eugene W. Illing (1870-1947), sometimes called Judge Illing, who founded in 1909, Illings Theatre on the northeast corner of Washington and Porter, which is now the site of the First Baptist Church of Ocean Springs.

***Bunny Illing was born Alvin J. Illing (1903-1978).

One of everything

When I was a boy growing up in Ocean Springs they had one of everything, no matter what it was. In the days that I'm talking about, we didn't even have electricity. You had oil lamps, and you'd take your little oil can in the daytime and go down to the grocery store. The can had a screw top and a little spout, and when you got your gallon of oil in there - which was about a nickel or a dime a gallon, it was very cheap - then to keep your oil from splashing out, the grocer would put a potato on it! That's what they did - they'd stick a potato on the spout so the oil didn't come out. The only thing they had more than one of around Ocean Springs was grocery stores. A. C. Gottsche (1873-1949) had one, E. S. Davis (1859-1925) had one, and W.S. Vancleave (1871-1938)- all of them are gone now. I think the building of Gottsche* is still there. But then when a fellow like me got home with my can of oil, then it was my job to see that all the lamps around the house got filled up with oil for the night. Electricity and all that came along later, much later. When I left Ocean Springs we were still using oil lamps. Somehow or another those lamps were adequate; you were used to them. That was what you had, that was what you were used to, and that was it.

Everything around our house was woods**; there was nothing built up. Not only did we have no electricity, we had no gas lines - we didn't have anything like that which was good in one way - you probably couldn't pay for it anyhow. Of course, you didn't worry about that either, because you used a wood stove and you could go out in the woods all around you and get all the firewood you needed. Of course it was work, you had to work; but anybody willing to do a little work around Ocean Springs, he could eat. You could take your net and go fishing or catch crabs. Even at a low tide you could go out there with a knife and open up some oysters and get fried oysters; I did it plenty times - go catch shrimp with my little brail net, and things like that. You could live, even though you had no money. Nobody else had any, so you weren't out of line.

The baker

We had one baker; he used to deliver bread - that was Frank Schmidt (1877-1954). He had a horse and wagon; he baked French bread and you could get your bread delivered. Every now and then, whoever was driving the horse, the horse would run away; the driver could do nothing with him and would probably fall out of the wagon, and so would the bread he had. So the horse would go back up to the bakery, go back home. Benny Seymour (1907-1969) had that job for a while. The horse ran away with him one day, and he got all skinned up and quit.

The butcher

My first job was with one of the Eglins who was running a butcher shop. It wasn't really that they had a monopoly on that; it was just the way it worked out - they hadn't tried to. My salary was $3 a week - and I had a horse to ride. The horse's name was Daisy. I didn't care much about the $3, but I sure did like having that horse to ride! She was a blaze-faced mare; she had a white blaze down her face. But I couldn't control old Daisy at all. I was telling Mr. Eglin about that one time, and he told me that was because I wasn't wearing a spur. Then he put a spur on my left foot - only one, I didn't have two - and every time I tried to make Daisy go ahead or do something, and she paid no attention to me, I just touched her with that spur, and that changed everything! That went on for a while, but I wasn't making enough money. But I liked having that horse to ride. I even learned how to saddle her.

News boy

I got another job as paper boy, delivering The New Orleans States Item. I used to go to the depot; the train would bring the papers in. Somebody else had The Picayune, but it was a morning paper.

Juvenile jaunts

On Hallowe'en, the bunch of us kids roaming around there were going to get into some kind of devilment. Old Man Rupp was the town marshal, and it was his job to maintain order. Don Tardy and I and all the rest of us about that age, we knew he was watching us; so what we would do was, part of us would go hide where he couldn't see us, and the rest of us would sneak on off like they were going to do something, and he would be following them and we would be doing the devilment. He said afterwards that he had followed us around trying to catch us, didn't have any luck and decided to go home. He said he pulled pine logs away from his gate till he got tired, then jumped the fence to get in!

I don't know whether we were any worse than any other bunch of kids. Over at Vancleave's, Don Eglin (1908-1986) had a crate of chickens - they used to sell live chickens or anything like that. He busted one part of the crate and jammed it against the door so the chickens couldn't get out. When Mr. Vancleave came the next morning to open the store, he had to pull the crate away from the door to get in, and when he did all the chickens got out! We were around there, you know, and we even helped him catch the chickens.

Down at the drugstore, Ocean Springs had two drugstores at this time, they used to get ice cream in metal cans, and when one was empty they'd set it outside. Matt Huber (1892-1968) had one of the drugstores***, and a bunch of us went around there one night and got a bunch of those cans and brought them around to Matt. We were getting a nickel a can for bringing them in to keep us from fooling with the cans, and he'd bring them in, he'd put them back out there, and we'd go get them and bring them back to him. Well, you know, we didn't have anything to do.

We went down to Fort Bayou one night and pulled a skiff out of there. A bunch of us carried that skiff all the way up into town and put it in front of an automobile repair shop, a garage**** they had there. He had a faucet outside where you could get water for your radiator, and we put his hose in the skiff, turned the faucet on, and let the skiff fill up with water. Well, he had a skiff there full of water next morning. They knew what we were doing; they were threatening us, even going to issue orders to shoot us down, but nothing like that ever happened. And that was life in Ocean Springs.

Of course there were other things around there. We used to go out and pick blackberries, fellows like me and Don Tardy and Sidney Woodcock (1905-1940) - that was the three of us who were in the same class in school. It was getting around Christmastime one time, and they wanted some moss to decorate the school. They picked me, Don, and Sidney to go get the moss, because we knew where the moss was! We missed pretty near the whole day of school: that was fine with us, we didn't care. We came back with sacks full of moss. They chewed us out about it and wanted to know, "What do you think we're going to do? Are we going into the mattress business or something? We just wanted a little moss to decorate the school!" But that was a good enough excuse, you know; it took a long time to get that much moss. We told them we had to go way down to East Beach to get it (of course we really didn't); that's where the most moss was.

Swimming and Old Fort Bayou

We used to go swimming in Fort Bayou because the water was deep -- around where we used to go, somebody said it was 20 feet deep, but I don't know how deep it was; I only know I never did hit the bottom. We'd go there because we figured the swimming was better, and the water was deep enough that we could dive. It never meant much to me; I never cared much about the diving; but there were some of them who loved to dive. Out in front of Ocean Springs, it was so shallow that we could walk around with our feet on the bottom; there was no way we were going to dive out there.

Every now and then, we'd have one of the fellows who would be a very poor swimmer or couldn't swim at all. We would take an empty jug, put a stopper in it, and tie it onto him so he couldn't sink. The tide created a current coming up the bayou and back out. Whenever he seemed to be getting a little bit too far away from the bunch that was swimming, we'd swim out and get him and drag him on back. But the whole time he was in the water, he had to have that jug tied on him, or we wouldn't let him in, because we weren't going to be responsible for him drowning.

There were times when the Fort Bayou bridge had to be opened so a larger boat could get by. The only way the bridge tender had of opening the bridge was a crossbar with a square fitting that would fit over a piece in the bridge, and this would operate a cogwheel that would open the bridge. After the boat got by, you'd walk around with the crossbar the other way and it would close the bridge. It never did happen very often, because there was not too much traffic out there then. Mostly people would use skiffs or smaller boats that could go under the bridge. So the bridge tender didn't have too much to do.

At one time the bridge tender was the grandfather***** of my first cousin Ambrose Fayard (1906-1986). Later on he got a job on the railroad, keeping the big water tank filled up for the engines. In those days, every train stopped in Ocean Springs, because the engine had to have water. In between trains, he had a two-cylinder gasoline pump that he used to refill the tank.

So it sort of went on like that; that was the general idea of juvenile life in Biloxi and Ocean Springs. Every now and then, even when I was living in Mobile, I used to run down that way and the old gang would get around there and we'd get together over at Benny Seymour's or Ambrose Fayard's house. One night we were over at the Seymour's on Dewey Avenue- that's Aunt Caroline's house. She was Caroline Mathilda Domning (1886-1969), my father's sister, who married Frank Seymour (1884-1933)- and they were having a little party down there and were going to make some eggnog. We had some moonshine whiskey and one thing and another, but they didn't have any eggs. So they picked on me and Benny Seymour to go over to Mrs. Doucette's - she had chickens - and to get them a dozen eggs. It was kind of chilly too, and we'd been drinking a little moonshine. It was all right as long as we were out where it was nice and cool; but as soon as we got in that house and it was hot - oh, boy. She brought a bag of eggs out and set them on the table, but neither of us was in any condition to pick the eggs up. And Mrs. Doucette****** knew Mama, and she was asking me all about Mama and I was trying to answer the questions, and Benny kept getting wobbly. Finally, he knew I wasn't going to pick up the eggs; I was waiting on Benny to pick them up. So he made a pass at the eggs, and instead of catching them he knocked them off on the floor.

"Oh! I'll have to get y'all some more eggs!"

Benny by that time had picked the bag up with the busted eggs: "No, they'll be all right like they are!" And we both took off and went on back over there, and they sort of strained the eggshells out of them and made the eggnog anyhow.

*The former A.C. Gottsche store building, which was erected in 1913, is extant at 809 Washington Avenue and is the headquarters for Blossman Gas Inc.

**The B.F. Domning home was built in 1913 and is extant at present day 504 VanCleave. The land upon which Freedom Field, which is near the old Domning home on VanCleave, was constructed in 1949 has been described by others of this era as densely wooded corroborating the statement by Rip Domning.

***The Huber Drug Store was situated in the Farmers and Merchants State Bank on the southwest corner of Washington and Robinson opposite Marshall Park.

****There is a high degree of certitude that Mr. Domning is referring to the business of Claude Engbarth (1893-1967), which opened for business on Washington Avenue in June 1922. The old Engbarth garage building was demolished by Blossman Inc. in January 1971. Today, Miner's Toy Store is located here in a new building.

*****Rip Domning is referring to Leonard J. Fayard (1847-1923) who was appointed the first bridge tender of the Old Fort Bayou Bridge on January 1, 1902.

******Mrs. Doucette was born in New Hampshire as Clara Moore (1866-1933). Her husband was Fred Dusette (1866-1934), a native of New Haven, Michigan, a small hamlet near Detroit. At Ocean Springs, the Dusettes raised chickens and sold eggs and pecans from their farm on the old Pabst place which is extant on the south side of Calhoun Avenue. This cottage and land today are probably in the Estate of Cecelia Buechler Fink (1909-1999).

Hunting

We used to like to go hunting; and one of the principal things we would hunt was wild ducks. I always claimed that I am the only duck hunter in the whole world who's batting a thousand: I went duck hunting once in my life, I shot twice, I killed two ducks, and I ain't been back! I've never done anything to upset that record.

The way it all happened was, I borrowed a double-barreled shotgun from one of my uncles and we went duck hunting one morning at the duck ponds on Horn Island. It was drizzling rain, sleeting - the weather was terrible. I was out in this marsh, bogged up to my knees, with a pair of hip boots on, wondering What in the hell am I doing out here in this marsh, in this mud, on a morning like this, getting all wet ...? As I looked up, I saw two ducks circling around, and I figured they were going to come light on this pond I was looking into. I stooped down, and when I did I sat down in the mud. Sure enough, here comes one of them in there, and I shot him; and this other duck came following in behind him. I shot the second time and I killed the second duck. They fell into the pond, and I took a long stick and pulled them in. I picked them up, took my shotgun, and went out on the beach.

The rest of the gang that I had been with had gone on down further where there were some more ponds - I could hear them shooting down there. I was all wet and mad and one thing and another. I had a little bottle of moonshine with me. Because it was drizzling rain and sleeting, it was hard to get a fire started. I used most of that bottle to get my fire started; I had picked up some driftwood on the beach. I drank what was left in the bottle (which wasn't much); after I got the fire going, I needed the rest to warm me up.

The rest of the gang came on back, and they had armloads of ducks - it had been a good hunt. They looked at me and they said, "You only got two ducks?" I said, "Yeah, and the empty shells are still in the gun." As far as I was concerned, my duck-hunting days were over.

Fishing

I was quite young, only eight years old, when my father was killed in a railroad accident in March 1915. We were living in Mobile, Alabama, when the accident happened. The only thing I knew about it was they found him on the railroad tracks near Lake Catherine, Louisiana after his train was gone on by and he wasn't even missed yet. They got on the line - of course there was no such thing as radio in those days, but they had telegraph operators all the way, and they just telegraphed ahead of the train that was on its way to New Orleans to tell them they were short a crew member. He was a brakeman. It was the train that was coming along behind them that actually found his body on the track, and that began the whole thing.

As I said, we were living in Mobile at the time, but then we moved to Ocean Springs because my father was building a home for us there; but it wasn't quite finished. But it was finished enough to be able to be lived in, and that's why we came back, because our income would be considerably reduced - well, maybe I should say it was eliminated. Because I was the oldest and I was only eight years old. I didn't try to go out and get a job at that time, but I doubt if anybody would have hired me anyhow. So we came back to Ocean Springs, because my mother, Alphonsine Beaugez Domning (1882-1965), was originally from Ocean Springs and she was moving back among family. She was the second of the six children of Alphonse Beaugez (1860-1942) and Caroline Seymour (1858-1933). My grandfather Beaugez was from New Orleans and came to Ocean Springs in 1872. All that I recall of my grandmother Beaugez is that she was very small, uneducated, and a good cook.

My mother had four brothers. Alphonse Manuel “Manny” Beaugez (1887-1945) was a carpenter. Then there was Henry Beaugez (1889-1963), Mose Beaugez (1891-1973), and Herbert Beaugez (1895-1954). I also had an aunt, Rosa Mary Beaugez (1884-1937). She didn't go to school as far as I knew; she stayed home. My grandmother, Caroline Seymour Beaugez, was very sick - in fact, she spent most of her life that I knew anything about in bed; she was bedridden, and Rosa took care of Grandpa and Grandma Beaugez. They were very poor.

Henry and Mose Beaugez were the fishermen of the family. They made practically nothing. Herbert left home and went up north for a while, I think, to Akron, Ohio; then the Depression came along and he came on back to Ocean Springs and moved in with my mother. Why he came all the way from Akron, Ohio to Ocean Springs looking for a job, you figure it out. In the meantime he had gotten married and brought his wife, Lillian Pearson, too. The house we had on VanCleave had two bedrooms. That meant my mother and all of her four kids had to sleep in one bedroom, and give the other one to Herbert and Lillian. He had no job; what was he going to do in Ocean Springs? He finally wound up going to the Rigolets too. He worked there for a while; then the shipyard over in Pascagoula opened up, and he was working at the shipyard when he died.

Shrimp seining

When I was considered big enough I had to go fishing my uncles, Henry and Mose Beaugez,. Whether I wanted to or not didn't make any difference. In my day we needed a four-man crew; and we could not fish in deep water, because we had to set the net out and had to get overboard to pull the net back in. So the way this was done, we had two skiffs that we were towing behind the boat. One of them had this big net, which was probably 600 feet long. We called it a seine. There would be three men in there, and one man would be left aboard the big boat; because then wherever we stopped, he would bring the big boat in place with the other empty skiff behind. And then we had a man in the bow of the skiff, one man rowing, which was usually me, and the other fellow laying up taking it easy on top of the net; and we were rowing along close ashore, maybe not too far out, until we began to find a spot of shrimp. Then we would circle around with the boat and see just how and where the spot of shrimp was and maybe how big it was.

Then we would get the skiff in position, and tell the man that was laying up there on top of the net to get overboard with one end of the net, on which we had a long pole which we called an arm pole. And then he would get overboard and shove one end of this pole down in the mud and hold it so he could start pulling the net off of the boat, while one man was rowing the skiff and the other one still trying with the small brail net to circle this bunch of shrimp. The seine net was nothing in the world but a wall of webbing; one end had a long rope on the top which had corks on it, and that kept that end afloat up on the top of the water. The bottom end also had a line or rope on the net, but it had lead on it so that it would sink to the bottom. Then the man that was at the end where we started getting over-sometimes it was me, so I'll say that it was me so I can describe it maybe a little bit better. After I had pulled enough of the net out, to where I didn't have to hold it anymore, then I was supposed to pull this arm pole up and start pulling the net ashore by myself - and that was pulling a 600-foot net-of course it wasn't all out of the skiff yet.

But finally, when we had the whole net overboard, then there were two men on the other end, and the skiff, which was now empty, which we called the seine skiff, because that's the one that carried the big net. Then they would start working ashore, and the man that was left on the big boat would bring it and stop it and anchor right outside of where we were going to be working, right close to the net. Then he would come ashore in the other skiff to help me. That put two men on each end of the net. We dragged the two ends together up on the shore, because we weren't working in deep water. And then when we got that done, then we had one man on each side of the net, which we called the lead-line man; in other words, he had to put his foot down on that lead-line to hold it on the bottom, and he would pull this way. The other two men were pulling on the cork-line and bringing the net in; and that's the way it went on until we got that whole net pulled in to where we were.

This net had built into it, in about the center of the net, what they called a bag, which was like a big trawl or a big envelope or something, that the shrimp would go into as you closed the net. And so you would just keep pulling the net that way - and that was hard work; don't let nobody hand you no stuff. The lead-line man kept the bottom end of the net on the bottom so the shrimp couldn't go underneath; and the corks on the top kept the net stretched like a wall while we were bringing it in. And it came in very slowly. When it got there and we were able, by pulling the net in, to force the shrimp into the bag, then we would pull the shrimp and work them on down into the bag until we had them to where we could bring the empty skiff alongside; and then we would work the bag up and scoop the shrimp out of the bag into the empty skiff. Of course, then our work still wasn't done because we had to put the net back in the other boat. So you can see by that that it took a lot longer to do that than it's taking me to tell you, and was a lot harder work!

It was because of that, and the fact that there were so many of the smaller boats that were always working along in shallow water, that the shrimp were either caught up or they were moved out into the deep water where we couldn't get to them. So, over the years, that was why they developed the trawl, which they could pull in any kind of water - deep water, shallow water, anywhere - so the poor shrimp didn't have much chance. I imagine that's one reason why today there's not more shrimp than there is: because pulling the trawl behind a boat has a tendency to close the mesh up, whereas in the other net the mesh stayed open and the little shrimp were able to filter out; but in this way you caught more of the little shrimp. And that is what actually, in the final analysis, got the shrimp down to where they are today - well, that and the fact that there are an awful lot more boats out there.

But I never did make any money fishing; and I never did get along with my kinfolks; so the whole thing was doomed from the start. Anyway, there were two or three things to begin with that sort of led up to the final deal. One of them was that after the day’s work of fishing was done, I, being the youngest and all that, was not supposed to get tired. Everybody else was supposed to be tired, and they were going to find them a comfortable place on the boat, which had no sleeping arrangements at all; but it didn’t make any difference – you’d just sit down and go to sleep wherever you wanted. And, like I said, being the youngest I was detailed to steer the boat, to bring the boat home. Well, I could do that all right; I knew how to handle that part of it. But I was tired too. And one of my uncles, who was considered the captain on there, his spot on there to take his nap was right flat up on the bow, because that’s where you got all the breeze. And I’m down here at the wheel steering the boat, nodding off. Every now and then I’d wake up and bring her back on her course, until we were coming along the beach down by what we called Pointe-aux-Chenes, and one time when I nodded off I didn’t wake up. The next thing I knew, the boat had swung off course and headed right flat into the shore; and the next thing we knew was when she piled up on the beach – WHUMP! My uncle who was sleeping up on the bow fell off right in front of the boat; he thought he was a goner.

But the boat wasn’t going anywhere; it had plowed into the sand. About that time everybody was awake, so we all had to get up. The boat was an old model, and we didn’t have any clutch in it to reverse the engine; you couldn’t do that. So all we could do was stop the engine and then get overboard, get all around the boat, and push her off into deep water again, then start the engine to come on home. Well, I really caught hell about that from all concerned; and being just a kid, what could I do about it?

More water tales

Well, that was just one of the situations that led up to my leaving home. We used to have a bit of a job starting the boat - nobody seemed to be taking much care of the engine anyhow, and it was kind of hard to start until it got warmed up. Well, my job when we came aboard was to take the anchor aboard (we usually pulled up to a stake, dropped the anchor by the stake, and then tied the boat to the stake so that she would be secured by both the stake and the anchor) - my job was to get her loose from the stake, haul up the anchor and get it aboard, and just hold on to the stake until the engine got started. Then I was supposed to push away from the stake, and whoever was steering the boat would go ahead. That was the way we had to do it; and so I started out by getting my anchor aboard and holding on - I would never clear up the lines on the deck until we really got underway. So I was just sitting there hanging on, and they were down there cussing and fussing with the engine, trying to get it started. Finally it started, and they hollered "Shove off! Shove off!" So I shoved off from the stake, and she ran maybe a hundred feet and the engine conked out again.

So here we are drifting; now they've gone back to cranking the engine, and I'm sitting up there on the bow. We had run away from the stake; I didn't have [any way to stop] the boat [from] drifting. My uncle who was supposed to be the captain on the boat came up and looked around and jumped all over me, and said, "Can't you see this boat's drifting ashore?"

I said, "Well, what do you want me to do about it?"

He said, "Throw the anchor overboard! Anchor till we can get the engine started!"

Of course, when we went out for the day we all had our dinners in our lunch buckets. Everybody else, including me, had set our lunch buckets up on top of the cabin. But Mose Beaugez, he was the captain, had set his lunch bucket right on the bow when he came aboard; and so when he jumped all over me and cussed me out and fussed at me about throwing the anchor, I threw the damn anchor overboard and his bucket got tangled up in the anchor line and overboard goes the lunch bucket! Well, he jumped on me then with both feet. I had about all I could take then; so I just secured the anchor line onto the boat and I jumped overboard. I knew where I was, and the water wasn't all that deep where I was. Then he really got after me.

"Get back aboard this boat!"

"I'm not coming back aboard! I quit!"

"I'll tell your mama on you!"

I said, "I'll see her before you will." So I just kept on wading ashore.

He told me, "Well, if you're going up there, tell Rudolph Ladnier (1900-1936) to come down here and take your place!"

I said, "If you want him, you go get him! I'm going home." So I did; I just waded ashore.

Mose said, "What am I gonna do for lunch?

I said, "Eat mine; it's up on the cabin where yours oughta been." It was just about daylight then. We weren't very far offshore. I went on home and told my mama about what happened. I got me some breakfast and a dry pair of overalls.

A PISTOL-PACKING PRIEST

There was a three-room house that we were using for a school. Father Irvine, a great big Irish priest who was stationed there in Ocean Springs, taught the catechism class. He always came armed with a nice big switch; so we learned our catechism!

One day, one of the boys, Joe Wieder, got rather unruly, and the sisters couldn't handle him. They went and got the priest, and the priest gave him a whipping. The outcome of that was, the next day Father Irvine was over at the school; and Joe Wieder's daddy showed up and told him, "Father, I heard yesterday you gave my son a whipping. I'm down here to give you one now!"

The priest looked around at him, pulled his coat off, threw it aside, and said, "Well, I guess we might as well get started!" But I never heard of no fisticuffs actually ensuing. I never heard of anybody jumping on that big Irish priest, either!

He had a motorcycle; the Church couldn't afford him an automobile. So he used to go visit all the parishioners on his motorcycle. He was well liked.

Right across the street from the church lived some people by the name of Rosambeau. Leo Rosambeau had a little grocery store there, and he had some chickens that would come over into the churchyard and dig up Father Irvine's flowers; and he didn't like that. When he'd catch one of Leo's chickens digging up his flowers, he'd go inside and get his pistol, and shoot him. It wasn't a very big gun he had; probably a .32 caliber, I don't remember.

Well, Leo didn't like that. But when he complained, Father Irvine told him, "Those chickens have got to come all the way across that street and into my yard to dig my flowers. They ain't got no business over there; you keep 'em home! Every time I catch one, I'm gonna shoot him! And don't get in the line of fire!"

Well, I don't know how long that went on; I just heard about all this. But that's another war Father Irvine won, because he was right. After Father Irvine had shot about half of Leo's chickens, Leo decided he'd better keep them home. He finally found the hole in the fence where they were getting out, and

patched it.

A DEAD WHALE*

One time a whale, I don't remember what kind, had been found dead somewhere south of the barrier islands out in the Gulf of Mexico, and had been brought in to the north side of Deer Island, which was the side facing Ocean Springs. I was living in Ocean Springs at the time. They had a schooner tied up on each side of the whale, so you could see him in there between the two boats. Ocean Springs wasn't that far away; not more than a mile at the most. People were wanting to go out and see the whale; whales were very rare there on the Gulf Coast. I had a chance to use a small sailboat, so I could take maybe four passengers for 25 cents apiece and sail over to where the whale was. It beat rowing a skiff, which some people did. Twenty-five cents was a pretty good price in those days.

That went on for a while; but the whale, being dead to start with when they found him, was beginning to "make his presence known." They didn't know what to do about the whale, but the local authorities told them they didn't care what they did, they had to get him out of there - he was creating too much "disturbance." I think one reason why the whale was left at Deer Island so long was that there was a bit of controversy as to who owned the whale. The ones that found the whale said it belonged to them; and then there were others who said no, the whale belongs to us. And so it was actually while the fussing and fighting was going on that the whale began to "make its presence known."

So they took the whale over from Deer Island to Horn Island. From there on, the only thing I know is that somehow or another they extracted some whale oil or something from it - I don't know what they ever did with it. In the final analysis, the remains of the whale - the backbone and the head part with the big jaws - they brought them in to what we called the Naval Reserve Park in Biloxi. In later years this park was absorbed into Keesler Field. They had taken these whale bones and put them all in a line - the head, vertebrae, and all in a line. According to the information I have, over the years these bones gradually disappeared. They say that some of those vertebrae from the whale made very good flower pots or something to plant flowers in; and I guess because of that those vertebrae dwindled and faded out of existence, and wound up in somebody's flower garden - not any one particular person, but whoever could get away with the vertebrae they wanted!

They tell me I don't know about this at first hand that also at the Naval Reserve Park they had a couple of animals, and one of them was a bear. Somehow or another the bear attacked the animal keeper out there and killed him. So then they had to get rid of the bear.

Conclusion

So that gives you a general idea of growing up around there - what growing up we did - around Ocean Springs. There were people who had orange orchards and pecan orchards; we'd go sit down in the orchard under the trees and eat all the oranges we wanted. Nobody said anything, didn't bother with us. And that harbor - you know where the harbor is in Ocean Springs? Well, in those days it was nothing but a ditch; we used to call it the Mill Dam Bayou. We'd go down there, and maybe somebody had a few oysters in a skiff; we'd open them up and eat the oysters, things like that. But that's the general idea, that's the way it was; we had to do something. What schooling there was going on there, we weren't too interested in that.

This concludes “Reminiscences of Ocean Springs” by Emile F. “Rip” Domning who was born here in 1907. Many thousand thanks Rip for a great journey back to the early decades of 20th Century Ocean Springs. Your contribution to our local history is greatly appreciated by those who care and love our wonderful, oak-bound village on the bay. Emile F. Domning (1907-2005) expired at Burtonsville, Maryland on May 21, 2005. He was staying with Daryl Domning (b. 1947), his only child, when he fell on May 2, 2005. His death resulted from injuries sustained in his accident.(The Sun Herald, June 3, 2005, p. A-7)

Caroline M. Seymour

Caroline Mathilda Domning (1886-1969) was born at New Orleans on December 15, 1886. In October 1906, she married Francis Joseph “Frank” Seymour (1884-1933), the son of Narcisse Seymour (1848-1831) and Caroline V. Krohn (1847-1895). Their children were: Bernard Seymour (1907-1969) married Theodora Smith (1910-1978); Amelia Seymour (1909-1964) married Vernon R. Goodwin (1905-1974); Oscar L. Seymour (1912-1964) married Lula E. Ramsay (1914-1974); and Milton J. Seymour (1917-1974) married Clara G. Roberts (1921-1972).(Lepre, 2001, pp. 102-103)

Frank J. Seymour made his livelihood on the waters of Biloxi Bay and environs toiling with his brothers, Hugh C. Seymour (1876-1913), John R. Seymour (1879-1938) and brother-in-law, Philip M. Bellman (1872-1927), to catch fish and shrimp and to harvest oysters and turtles, as part of the Narcisse Seymour & Sons organization. His father was a pioneer of the seafood industry at Ocean Springs albeit it was small scale compared to the industrial scale seafood processing in Biloxi, which has been called “the Seafood Capital of the World”, but with no statistical data or other proof to substantiate the claim. The Seymour’s oyster shop was situated at the foot of Washington Avenue. In time Hugh C. Seymour, John R. Seymour, and Philip M. Bellman opened their open oyster shops on the front beach at Ocean Springs, while Frank continued to work for them as a fisherman.

Dewey Avenue

Narcisse Seymour acquired Lot 7-Block 41 from Charlotte F. Cochran in October 1902. He sold it to his daughter-in-law, Caroline M. Domning 1887-1969), the wife of Frank J. Seymour (1884-1933), in February 1914. Their son, Oscar Seymour (1912-1964), acquired it from his mother in 1942. After Oscar Seymour and family moved to the Veillon-Fields Cottage at 300 Ward Avenue in 1944, he sold it back to her in January 1946. Mrs. Seymour then conveyed the home to another son, Bernard P. Seymour (1908-1969), in August 1958. This old Seymour residence at 212 Dewey Avenue was acquired in July 1991, by Larry and Celeste Maugh. They did an excellent job of preserving and improving this historic property, a trend that has continued under current owner, Lynn Linenberger.

Amelia F. Ryan

Amelia Florence Domning (1889-1954) was born at New Orleans, Louisiana, the daughter of Emile Domning (1850-1918) and Christina Elizabeth Seikmann (1848-1933). She married Frederick “Fred” Joseph Ryan (1886-1969) on January 17, 1911. Before her marriage to Fred Ryan, Amelia worked as a cook for Charles B. McVay (1845-1923), a wealthy Pennsylvanian, who resided on Lovers Lane at present day 319 Lovers Lane, which is known today as “Conamore”, with his spouse, Annie H. McVay (1850-1920+). The McVays also had a chambermaid, Cora J. Mon (1879-1965).(1910 Federal Census-Jackson Co. Ms. T624R744, p. 1a)

City Ambassador Fred J. Ryan

Fred J. Ryan (1886-1969) was born January 26, 1886, the son of a local fisherman, Calvin Ryan (1850-1900+), and Odile Miller (1853-1888+), the daughter of George Barney Miller and Marie Delphine Bosarge. His siblings were: Victor Ryan (1877-1877), John Ryan (1881-1943), Charles Richard Ryan (1883-1939), and James Camille Ryan (1888-1967). As a young man, Fred Ryan like many of his peers worked on construction gangs for the L&N Railroad. He learned his trade well and by the late 1920s, he was employed by Robert W. Hamill (1863-1943), a Chicago entrepreneur, and Clarence W. Gormly (1882-1957), the founder of Gulf Hills, to construct roads, bridges, and piers in the Pointe-aux-Chenes and Belle Fontaine areas of the county. Ryan supervised a crew of fifty Black and nine White laborers.(The Ocean Springs Record, January 16, 1969, p. 14 and The Gulf Coast Times, July 22, 1949, p. 5)

With his construction days in the past and after a short stint in 1934, as proprietor of the F& H Bar with Henry J. Endt (1910-1989), Fred Ryan and spouse began a small seafood restaurant cum lounge and dance hall, which he built adjacent to his home at present day 1314 Bowen Avenue. In April 1924, Christina S. Domning had conveyed to her daughter, Amelia D. Ryan, “my homestead”, which was the original Emile Domning (1850-1918) place on Bowen Avenue. .(JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 53, pp. 624-625 and The Jackson County Times, May 5, 1934)

An account and recommendation to dine at Ryan’s Seafood Restaurant was sent by a patron of Ryan’s to Duncan Hines (1880-1959), the Kentucky food critic and Craig Claiborne (1920-2000) of his day. The patron’s description of Ryan’s was published by Captain Ellis Handy (1891-1963) in his “Know Your Neighbors” series of The Gulf Coast Times, a most valuable contribution to the preservation of our local history.

…..two blocks from the business center of Ocean Springs and away from the highway(Government Street at this time), is a barn like structure called “Ryan’s”. There is a parking space in the rear for curb service or tables in side. Fancy frills are out of place at Ryan’s. Oil cloth tables, paper napkins, and the bill of fare on the wall. But, oh, what food and hospitality!!! In seasoning and cooking, both Mr. and Mrs. Ryan are stars of the first magnitude. Ryan’s own special sauce is delicious with their seafoods, steaks, and chicken. And prices are ridiculously low. The stuffed crab specials, which Ryan’s are noted, are 5, 10, and 15 cents according to the amount of crab meat in the mix. Three of the five cent stuffed crabs with a cup of coffee or bottle of beer, is far more satisfying than a dollar dinner elsewhere. On a good day Ryan’s serve 700 to 800 crabs, their top was 1500.(The Gulf Coast Times, July 22, 1949, p. 5)

Ryan’s highlights